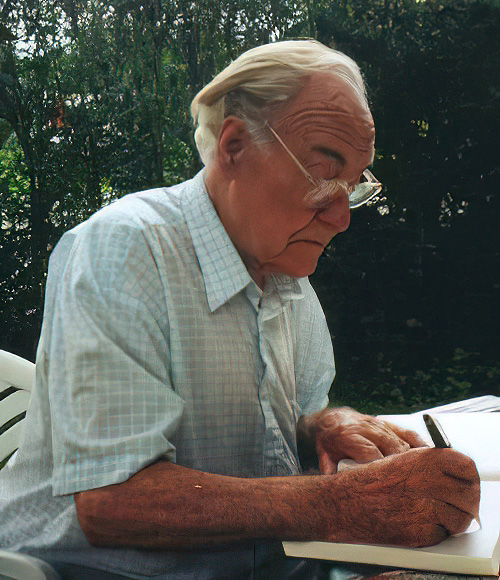

Interview with Knight's Cross winner and Platoon Commander of the schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 502, Paul Egger, credited with destroying 113 tanks, Landau, 1988.

Interview with Knight's Cross winner and Platoon Commander of the schwere SS-Panzer-Abteilung 502, Paul Egger, credited with destroying 113 tanks, Landau, 1988.

Paul: I was a youth growing up in Steiermark [Austria] and at first was envious of pilots who seemed to enjoy the freedom of being in the clouds; I knew that was my calling. Austria did not have the organized youth groups as the new Reich did, but there was enough support to get me training on gliders. In 1938 when we reunited with the Reich, my fortunes changed. I graduated and held a job as a clerk, but I was not fulfilled. When the reunion took place, I quickly left my job and applied to admission to the new Luftwaffe. I was accepted and placed in bomber training, flying a new type of plane -- a dive-bomber. Things moved quickly for me with training, and then commissioning as a pilot. Then war came unexpectedly, we believed the Führer would not allow the Reich to be pulled into any more wars, but circumstances spiralled out of his control. In August I had been assigned to KG51 [Kampfgeschwader 51 (Battle Wing 51) 'Edelweiss', was a Luftwaffe bomber wing during World War II which was heavily involved in the Battle of Britain]. We were moved close to the border and given daily updates on the situation with Poland. We did not have much time to train so there was a fear that we would have to fight with very little training or experience.

When war was announced it was very early in the morning, we were

briefed and given targets consisting of hitting railyards and military

installations. I remember being cautioned about ground targets, we were

advised many refugees would be clogging the roads and that they might be

mixed in with Polish military vehicles. I say this because the Allies accuse us

of deliberately attacking civilians, but we went out of our way not to attack

anything that could have civilians. An army unit logged a complaint against

me because I did not attack a Polish armored column, who then went on to

cause losses to a Panzer unit. It appeared there were civilian cars mixed in,

so I avoided attacking.

After Poland, I was given the chance to join a fighter wing, so I

accepted and trained on the Me-109 [Messerschmitt Me 109, a fighter plane] just in time for the French campaign. This

was a very hard-fought battle; we were outnumbered and faced an enemy

who had months to prepare. One of the great myths of the war is that the

Luftwaffe outmatched and outnumbered the Allies. It was the other way

around. We suffered horrendous losses; it was only the skill and bravery of

our pilots that won the day. I still feel the Spitfire and Hurricane were better

planes than the early Me-109. Even [Adolf] Galland and [Werner] Mölders, whom I met, agreed. They both told me the only way to win was to be think about what the

enemy could do, not what he might do.

During the Battle of Britain I was shot down three times and my

final time, after over 100 missions, I suffered a bad head wound that put an end to my

flying days. After this I was assigned to fighter staff.

What attracted you to join the SS? What was your impression of Hitler since

you were from Austria?

Paul: One thing that many Americans do not understand is that Germany and

Austria are so closely related in language and culture that many consider us

as one people. When you can go to either country and see the same

architecture, eat the same foods, speak the same language, and practice the same

customs, there is no real difference aside from small local customs. The Reich

was very successful under Hitler, an Austrian, so we wanted to join this

success as our nation was still dealing with the depression. He was looked

upon as a very great leader who saved Germany from chaos and restored

order.

I would see photos of the black uniformed SS men at rallies and in

trips to the Reich I would see them strolling with the prettiest girls. I always

thought it would be good to join such an elite group of men, I never paid

much attention to the racial ideals they believed in, but I did like that the SS

was trying to preserve Germanic history, something that was being forgotten

in the Weimar era. A comrade of mine had joined the Waffen-SS and really

liked this branch, so in 1941 I asked for a transfer and a chance to serve in

the SS. By this time, the Luftwaffe had more men than we needed, so this was

easy to accomplish.

The training in the Waffen-SS was very tough, our bodies were made

strong and our minds steeled for adverse situations. A strong bond with each other

was created and a firm belief in our cause was nurtured. I selected anti-tank

training as my next duty and was trained on the pitiful 37mm Pak gun, which

by 1941 should have been withdrawn from service. Even the instructors told

us it was useless, even in Poland. They taught how to use it to disable a Panzer

by carefully placing shots on the tracks, or turret ring. I became very good at

this, which was fortuitous for me later on.

What was the early war in Russia like for you?

Paul: When war with Russia broke out, I was transferred to a motorcycle

reconnaissance unit with my anti-tank crew. We had great success against the

Russians; the vast amount of prisoners we brought in was truly astounding. I believed victory would be swift. We were outnumbered but defeated every

counter-attack they threw at us, with heavy losses. The coordination with the

Luftwaffe worked like clockwork, whenever we encountered a Russian

position the planes appeared overhead and did their work.

I was assigned to the 'Reich' Division, as it accepted men from all

over the Reich, and there were many from Austria in this division. One

instance I clearly remember was outside Yelnya [Russia], we were moving forward

when suddenly the Russians hit us with a large tank attack. I was able to use

my 37mm Pak gun, hitting and destroying five tanks; our barrel was red hot.

We broke this attack, which caught us by surprise and outnumbered our thin

line by a large margin. I thought to myself how the Russian tank crews

seemed to lack the skills to avoid our fire; this made me think about joining

our Panzer arm.

I still remember how vast Russia seemed, endless roads and

landscape and many people.

Every town and village we captured still had

civilians residing.

They were very kind to us, as the communist-minded

retreated with the army. I remember being welcomed as liberators and we

were always given food and water. The people had nothing to fear from us

and we had nothing to fear from them. I was happy whenever we came to a

village with young women my age, especially when the weather was bad

because we were usually invited to stay in the small home with them.

Today it is said that the German Wehrmacht, and especially the SS, raped

Russian women. I can attest that that is not true in the least. I remember

making a comment aloud once in which I said some Russian women would

be nice to lay in bed with on a cold morning, and the next day I was called to

my commander's tent. He advised me that while he knew my talk was young,

innocent banter, we must always remember the Russian woman is a European

as much as a German woman and we must never disparage their reputation

by insinuating that they are easy or a trophy; he did not want it to look like

we craved Russian women as war trophies.

If a German soldier forced himself on a woman, he would be shot,

that was made very clear to us all, and I heard of a few men who were accused

of this and indeed paid with their lives. Russian civilians helped us more than

once, especially during the terrible cold during the winter of 1941-1942. It

was at this time I started spending time around our Panzer regiment and got

to know many comrades. I was getting the itch to join a new career field, one

in which there was no hauling a gun.

By late 1941 we were on the outskirts of Moscow and I personally could

see the minarets with a scissor periscope ['V' shaped binoculars used mainly by Panzer commanders]. We were that close to victory over

Russia, because I believe if we could have struck the capital and disrupted

the rail lines, it would have broken Stalin. The Japanese turned their backs on us after we signed a pact with them; I understand they were still upset we

supplied China early on. If they had struck from Mongolia with massed

armies, it would have prevented the reinforcements that hit us at the most

inopportune time. 'Reich' was mostly wiped out during the winter counter-offensive; it came as a big surprise as we believed Russia was finished.

I was lucky to be alive, we were over-run and the fresh eastern

Soviets were butchers, I witnessed them kill soldiers who had surrendered

and they seemed to go out of their way to be cruel. During a local counter-attack,

we recovered a village we had lost. There were around 40 civilians, when we

retook it, that had been killed. They had been labeled as traitors and the pretty daughter of

the family I stayed with had been raped and shot in the head. This was hard

to see and left a lasting impression on me regarding the Soviets. We quickly

lost the village again so we could not bury them, and I am sure the Soviets

then blamed 'Reich' for the killings.

[Above: Crewmembers of a Tiger of the schwere Panzer-Abteilung 502 in the summer of 1943.]

What was it like for you when you went to the Panzer arm?

Paul: After my experience with the Russian winter, I felt broken and fearful

that this war was going to expand out of our control. Once we declared war

on America, I recalled the stories the elders told of the first war, and how the

Allies used overwhelming force to bring them victory. It felt like this was

happening again. 'Reich' was pulled out of the front to refit and I had made

up my mind that I wanted to join the Panzer regiment, so I spoke to my

commander and he agreed. I was sent for training during the spring of 1942

and was put on a Panzer III. I liked the black uniform, as I walked along the

streets where our training was going on and I felt very elite.

I was assigned to the 8th Company and there we had the newer

Panzer IV; I was eager to get back in the fight. I was sent to France for more

training, and was impressed with the French way of life; it was laid back and

you would never know a war was going on. News from the fronts was good

again. After we shook off the winter offensive our forces were moving again.

'Reich' received new replacements and equipment, which was badly needed.

I remember by June 1942 all Reich units were together and we underwent

tough training as a new Panzer grenadier division. The infantry was taught to

rely on the Panzers and the Panzers to rely on the infantry.

I met a French woman whose husband had left her to flee to

England. I could tell she was sad and since we were close to the same age,

we became friends. We would go for walks and talk about life and our

experiences. I looked forward to seeing her on the weekends and was jealous

when comrades pointed out she was pretty and needing their company. She

became a good friend and a respite from the war.

I tried to stay in touch with her but later in the war it became harder

and harder, I would see her again before the Normandy battle, but that was

the last time. I tried to find her in the early 1960s and was told in confidence

by her neighbor that she had been attacked as a collaborator and beaten after

we retreated, so she fled and no one knew where she went. Her husband never

showed up, so perhaps they found each other and never went home. I still

remember her beauty and funny laugh; she was a good friend whom I hope

fate was kind to.

I did very well with the new Panzers and was promoted to

commander. It was announced Das Reich was moving out for the east again.

I was on the long barrel IV and was surprisingly anxious to get at the enemy

again, to pay them back for the winter of 1941.

Germany is accused of horrible atrocities, especially on the Eastern Front;

did you see any of this?

Paul: You have to understand what an atrocity is; it is deliberately being

cruel, especially to civilians. The Wehrmacht had very good relations with

the Russian people, there are millions of photos taken showing this was not

staged. We did not shoot prisoners as is claimed, they were valuable for

intelligence, and many joined the anti-Bolshevik armies fighting alongside

us. History does not tell their story today, but a vast amount of Russians who

were captured formed armies and helped us fight. Stalin asked to have them

all returned after the war, and most were murdered as traitors. Today the

Soviets inflate their war dead, and some of these victims are laid at our feet.

There were times when partisans, who could be a man, woman, or even kids,

were caught violating rules of war. In some cases they committed terrible acts

against us and their own people who helped us. When caught

they were tried by elders or military officers. If they were just guilty of

attempts to sabotage most were sent to camps. If found guilty of murder they

were hung or shot. The Allies like to parade the photos we took of executions,

which we were free to take, as proof of atrocities or war crimes; they were

neither. I never saw young people executed, unless they killed someone, they

were usually registered and turned loose.

In France, as you know, we are accused of burning down a whole

town, killing large amounts of hostages, and blazing a path of destruction. I

would like to set the record straight. While I was not part of the force who

went into the towns, I had comrades who were. The actions of the Maquis [French terrorist group supported by the Allies]

are nothing short of irresponsible decisions, war crimes, and terror against

innocents. We had to deal with soldiers murdered by non-combatants, sometimes in very cruel ways, and when caught they and anyone who helped

them opened themselves up to our legal response.

Oradour is an example where a whole town had been left without

occupation and it turned into a nest for the Maquis fighters. The whole region

had been left alone and was ripe for the Allies to recruit. Our columns were

constantly attacked on our way to Normandy, all by civilians, who were

committing crimes by fighting. A three-day journey took seventeen due to

this, the Allies turned civilians into criminals. Based on testimony from

German soldiers who had escaped from the Maquis, it was confirmed that

everyone seemed to be involved one way or another in these towns, men and

women. Usually when a Maquis was caught, they were just sent to prison

camps unless their act killed someone, then they were executed.

Oradour was a town where Germans were taken as hostages and

then brutally killed for no reason. This was one example of many in that area.

Many Alsace men were in Das Reich, so they spoke French, while

investigating and interrogating, all town's people were put into a church. A

fire started and burned out of control, with the help of illegal bombs,

mines, grenades, ammunition and explosives. My feeling is the Maquis may

have been trying to hide what was in the church and set it off, or wanted to

start fighting as many burned weapons were found later. Das Reich did not

have the equipment to put out the fires.

My point is that men of Das Reich did not kill innocent civilians

ever, and they did not set the church on fire, the Maquis had to have done

something that triggered it. It was never our aim to turn the people against

us and actions like this were unfortunate events that happened in the middle

of a large battle. Thus a true picture was hard to get as many men fell who could have told it. I know anyone who was guilty of helping aid in the murdering of

Germans was punished with execution, and that is no war crime.

You were in the heavy Panzer battalion with the Tiger, what was that like?

Paul: You must let me finish my earlier story. Das Reich was sent back to

Russia to help in retaking Kharkov; my Panzer regiment did very well. I

adapted very well to my new role as a commander and my crew worked well

together. We faced the T-34 [Soviet medium tank] mainly, the Russian crews lacked coordination,

but they came in droves, which was their strength. We would find ourselves

facing a whole battalion sometimes, but my gunner was very accurate, and

we started to accumulate a kill tally. This brought more and more confidence

and trust in each other and made us a formidable foe.

We were used as a fire brigade, repelling Russian attacks, then

moved to the Kursk area. Rumors abounded that we were going to hit the Russians with a large attack in the summer. We received upgraded Panzers and much needed equipment. When [Operation] Citadel started, we had had great success,

sweeping all opposition aside. The Russians outnumbered us by large

margins, but we kept pushing forward against incredible odds. I believe we

pushed the enemy back more than 55km if I remember correctly. We left

hundreds of wrecked Russian vehicles in our wake; we saw many American

made vehicles, and enjoyed captured C-rations. We treated the captured

Russians well and shared with them.

When Citadel was called off, we were livid, we felt like victory was

in our grasp. The Russians were being bled dry and we still had a lot of fight left despite heavy losses. It was a bitter feeling, but orders are orders, so we

obeyed. We stayed as a rear guard, fighting weak Russian attacks, then it was

announced we were going back to France to refit and rest; 1943 was a tough

year for Das Reich. I heard about the new heavy battalions being created so

naturally I wanted to join, and was accepted, as I had a very good reputation.

Many Panzer men from Das Reich went to the new 102 heavy Panzer

Battalion. I liked the Tiger; it had much better armor, a better gun, and

optics. The training was tough, but we felt very confident in these new

weapons and actually were anxious to get at the enemy again. We stayed in

France, as the rumors were that the Anglo-Americans were going to land

somewhere in France and we would be the first to face them.

[Above: Three pictures of the iron man, Paul Egger, who even WWII couldn't kill.]

What was the Normandy battle like?

Paul: We were in the south part of France when word of the invasion came. As I mentioned earlier, a journey that should have taken three days, took

seventeen as the Allies supplied the Maquis with every type of weapon you

could imagine. There were commandos and English spies with them to help

bring in air support. The 102nd Panzer was with Das Reich and went right into

action when we arrived, but we faced a strange battle, as the air belonged to the

enemy. We dared not move in the daylight hours, and had to stay hidden, they

attacked anything on the roads.

They used rockets which were very effective and accurate against

us, and their artillery seemed to have unlimited rounds, unlike ours which we

had to conserve, sometimes not firing for days. By the time we entered the

battle, it was already lost. Rommel's plan was to bring force in mass, as soon

as the landings happened, but due to infighting by the generals, this did not

happen. When the Allies seized the beaches, they had already won, as now it

was a war of attrition and we were outnumbered by a huge margin. Our

strategy was now to try to contain them and bleed them dry, but since they made resupply very difficult it was only a matter of time before their numbers

broke us.

I will tell you one observation about the battle that no historians will

mention today. The Allies fired so indiscriminately that the French paid a

heavy price. We would just be passing through a town or village and the

Allies would open up on it, not caring if civilians were out in the open, they

then excuse this by claiming we shot or executed the civilians. We did not

bother the French. In fact, many times they came to us asking for help for a wounded

family member. I remember a farmer came to our commander and said

American paratroopers had assaulted his daughter when they landed on his

farm and were left alone for a week and wanted us to lodge a complaint.

I felt bad for the French as their country was being laid to waste, but

this was a fight to save Europe and we urged all that we saw to stay in shelters

because if they were caught on the roads the Allies strafed them. I personally

saw many civilians dead due to reckless Allied shellfire and strafing. One

town had 15 of its inhabitants killed when a naval shell landed in their midst

while they were trying to decide if they should shelter or leave. We could

only assist in putting them in shallow graves, and our priest gave them a last

blessing.

It has been claimed that German units committed war crimes in Normandy,

did you see any of this, or do you agree?

Paul: No, I do not agree, and I did not see any German units breaking any

rules of war. We caught some saboteurs and enemy soldiers in civilian

clothes, who were promptly arrested and sent to the rear for the police and

Milice [a French paramilitary group formed to battle the terrorist Maquis] to deal with. What I did see was evidence of Allied war crimes, from

killing civilians to shooting surrendered soldiers. I also heard about field

hospitals being shelled, one from the HitlerJugend Division was overrun and

many wounded were shot. One personal instance was when I was looking

through field glasses and saw a group of SS men who had been overrun

surrender, and then they were shot down. I ordered my gunner to fire on the Allies, but

this only betrayed our ambush position and invited counter fire.

The Allies seem to like to portray anything they can as a German

war crime, I am sure they came upon many scenes where civilians had been

hit by Allied fire, but instead of admitting they made mistakes and fired on

civilians, it was easier to say the Germans killed these people out of hatred. I

can say I never saw any incidences of German soldiers shooting surrendered

Allied soldiers, I am sure there could be a few incidences, as tensions were

high and emotions could boil over. I did see a young SS lad punch a British

soldier and he had to be pulled away, for what, I do not know.

What was the rest of the war and the end of the war like?

Paul: After we were beaten in Normandy, and barely survived Falaise [the Falaise Pocket, where the Allies encircled the Germans to disastrous effect] we

were pulled back to the Reich to refit, and we were renamed the 502nd Heavy

Tank Battalion [schwere Panzerabteilung 502]. I turned to sports to keep my spirits up, playing soccer as

often as I could. By this stage of the war Germany was in ruins, nearly every

large town and city had bomb damage, yet spirits were high. We rested in the

autumn and by winter we were thrown into the Ardennes battle [the so-called Battle of the Bulge, as the Allies called it. This was no doubt an attempt to downplay the nearly successful German offensive. General Patton himself said that if the Germans had been successful it would have meant the war would have lasted into 1946 and perhaps even a negotiated peace.-Ed.] in the hopes to

stop the western allies, so we could concentrate on the Russians. This battle

was much like Normandy, we were vastly outnumbered, with no air support, and no

fuel reserves, but we fought nonetheless.

It was cold, and the weather was bad, but at least it kept the planes

grounded. We punched through the Allied lines, but the roads made the going

tough for large Tigers and wide tracks. We started well, then the fuel situation

became an issue, we struggled to get supplies, as the roads were clogged and

hard to maneuver on. By 1945, it was all over, we knew at this time that unless

a miracle happened, we would lose. We were sent to try to recapture

Budapest, but Allied air power made movement hard, and by now we faced

an enemy who outnumbered us by more than 10:1, with no artillery, no air

cover, and limited ammunition.

We failed to retake Budapest, suffering heavy loses, then were

moved up north by try to stem the onslaught on Berlin. I was awarded the

Knight's Cross by General Paul Hausser, but it was a bittersweet award. My

great crews made this award possible due to the number of kills we made

together. Due to the late stages of the war this was a very informal award, no

visit with the Führer, and I was right back in action soon after. Our Panzer

was very successful, even against the new heavy Stalin tank; I was a master

of ambushing them. We did end up getting knocked out of action and I was

in Berlin looking for a way out of the dying city.

The war was lost and I had no more to fight with, I was able to

escape Berlin with a large group and we made our way west. The hope was

to link up with remnants who could still fight, but we ran into the Americans

at the Elbe. They treated us well for the most part, but they did steal all my

belongings and medals. I avoided being sent to the Russians as I had fought the

Americans in Normandy and the Ardennes and they liked to get details of the

units fighting them. I was held illegally as a prisoner until 1947. Since

Germany capitulated unconditionally in 1945, all prisoners should have been

released, but the Allies refused to agree to a peace treaty just so they could

hold millions of Germans as slave laborers in Europe. They now claim we

were the ones using slave labor, which is false. I met many foreign workers while on leave and they were free to roam. I could tell they were well paid by the way they dressed.

[Above: It's interesting that we have all been taught about how those 'horrible Nazis' enslaved their people, yet their is no evidence of such and ironically, there is proof that the Allies did just that. In the United States workers lived in deplorable conditions, literal shanty towns. Britain was no different. The source of this information is the British themselves -- the Daily Mail and was reported first internationally by the neutral Swiss media. Have a look at the article found below. This is the cover of the newspaper where the article is found: The Guernsey Evening Press (No. 11,515), June 12, 1942. Note that these island newspapers are the only English language newspaper in the Third Reich. Guernsey is an English Channel Island, for those of you unfamiliar. Click to enlarge!)

[Above: Here is the article mentioned above - 'British Child Slavery - Wage for 50-hour Week-25/-'. Click to enlarge and read the full article!)

[Above: A lone unknown warrior stands atop an early Tiger code II of the schwere Panzer Abteilung 502, 1943. This battalion was one the most successful German heavy tank battalions, claiming the destruction of 1,400 tanks and 2,000 guns.]

The official report on Egger earning the Knight's Cross:

"On the 14.07.1944 the English took the heavily contested Hill 112 following hours of artillery drumfire and the liberal use of artificial smokescreens. In response SS-Oberscharführer Egger, Zugführer in the 1./s.SS-Panzer-Abteilung 102, immediately initiated a counterthrust through the thick smoke on his own initiative with 4 Panzer VIs. Despite the thick smoke Egger skillfully led his Zug into the flank of the enemy, and in the combat which followed a total of 14 enemy tanks and 7 heavy anti-tank guns were destroyed. A pursuit thrust after this gave friendly infantry the opportunity to once again attain the old frontline. Through these independently conducted actions SS-Oberscharführer Egger had a decisive share in the immediate recapture of the tactically vital Hill 112. During this action SS-Oberscharführer Egger and his crew personally destroyed 7 enemy tanks, and in doing so raised Egger's total of tanks destroyed to 68."

[Above: Paul Egger, all those bloody years behind him.]