Interview with Herbert Willy, a veteran of the Luftwaffe Flak-Regiment 23, who saw action on nearly every front of the war -- Czechoslovakia, Poland, France, Balkans, Crete, Russia, and Normandy. Kaiserslautern, 1989.

[Above: In Crete, the gunners of the 'A' gun of the 3rd battery of the Flak-Regiment 23 load shells into an 8,8 cm flak gun. Click to enlarge.]

Thanks for agreeing to come here to meet; it is a pleasure to meet you. I would like to start off by asking you how you came to be in the Luftwaffe, and the Flak specialty.

Herbert: Oh you are very welcome sir; I am pleased that someone young cares about meeting an old soldier. You know my wife and I were alive when Hitler came to power. We both lived in Berlin and it was a cold day I remember, but everyone was yelling in the streets and out waving flags.

I was an SS man in 1933, yes I do not tell anyone this, but here is my portrait taken in 1933 as an SS-Anwärter [a paramilitary rank which translates as 'candidate' or 'applicant'] in the 42nd with the honor name Fritz von Scholz [42.SS-Standarte Berlin]. I would guard speakers from the red front when they tried to disrupt a speech or gathering of the party. I can tell we had some spirited exchanges with those knuckle heads.

They were so anti-German, anti-religious, and anti-common sense. It amazes me to this day that anyone follows them, it's like a magic spell is on them or something. They are idiots with false understanding and hatred masked as love and human rights.

So how did I come to the Luftwaffe? In 1935 the Hitler government was able to throw off Versailles and make treaties with the Allies for peace. Part of this meant that Hitler could start to rearm Germany, a move that was very popular among many. Germany had been made weak after the war and there was a big fear of the Soviets and the red revolutions.

When it was announced that there would be conscription again, I went ahead and applied for admittance in 1937. I was accepted after going through the application and physical. It was nothing like joining the SS. There one had to be in excellent health, of pure Germanic blood, be tall, and be of good character, which I was.

The Luftwaffe on the other hand just said "come to us we are happy to have you", so I went in and said I need a place to hang my hat. I liked planes and thought maybe I could fly. I was wrong in that. I was assigned to a 2cm flak unit, in the 23rd Flak regiment which was put together in Czechoslovakia. We stayed there for awhile and drilled until we saw action in Poland.

Can I ask how it was in Czechoslovakia, how did the people treat you?

Herbert: Well in those days the country was a mess. Hitler had taken back the Sudetenland, and then later was allowed to come in and form the protectorate, where friendly allies to Hitler watched over the country.

The people were used to having other nations over them; they used to be part of the Hapsburgs and so on. We had Austrian men with us and they did not care for the Czechs that much. There had been attacks on the Austrian border farms by some bands of criminals they would say.

I would hear them say Hitler was too kind to the Czechs in only wanting a small part of the area, when he should have taken more to punish them. In spite of this I can tell you that the majority of the people seemed very happy and content. I spoke to a few you know; they spoke German, even with the Prussian dialectic.

Taxes had been very high for them, and Hitler, as in Germany, lowered their taxes. This helped the worker and now they had more left from their pay. There were incentives for their factories to make cars for the people, and they received tax breaks to buy these cars. My family owned a motor bike shop in Berlin, and overnight in 1933 we had more money from tax savings.

Where I was stationed there were dances and many bars we could enjoy. The ladies enjoyed the company of soldiers; they say they love men in uniforms. A comrade went on to marry a Czech girl a week before the war in 1939. We had no problems at all with the people. Agitators had all fled to other countries so here it was a peaceful place.

Can I ask you about the start of the war? How did the German people feel when war was declared?

Herbert: Shock. Shock is all that I can say. We did not want a war; the last war was still too fresh on everyone's mind. We had no hate for Poland or the west. We only wanted our place in the nations of Europe, and not to be told how to do things. What started it all was Poland and the guarantees from the English.

They had been given lands that were home to many millions of Germans who did not want to be Polish citizens. The Allies looked at it as "well if you don't like it move to Germany". They had lands which were in their families for hundreds of years, and now they were subjects of a new government.

This would not have been bad if that was all there was. The problem was Poland wanted them as loyal Poles and to cast off their German ancestry. Because many would not and openly agitated for a return to the Reich, they started to be attacked. I read about this, and I had a comrade who had fled Poland in 1938 and came to the Luftwaffe. He told about how bad it was for many Germans in Poland.

He would tell us in lively words how they were taxed unfairly, had land taken away, kids were bullied in mixed Polish schools. They would not allow German only schools and forced German children to go to Polish schools. He told us a girl who lived by him was killed by a Polish gang of boys. They beat her and she later died. They said they did it because they hated Germans.

In the end many former Germans fled to the Reich and told of these accounts, which sent Hitler into a path of war. It was his reason for attacking Poland, there was no Lebensraum ['living space'] or push to the east. He was defending the civilians who could not defend themselves. Polish bands also attacked parts of the border, much like right after the first war.

We heard about these attacks in the papers and on the radio. When we marched into Poland, we knew we were there for the right reasons. When both England and France declared war that shocked us all, there were no celebrations like in the first war. There was sadness and fear.

Can you describe what it was like to be part of the attack on Poland?

Herbert: Yes, we were moved close to the border, and we knew tension was high. We heard rumors that police units and patrols had caught some Polish soldiers sneaking across to mark maps to plan routes of attack on us. Can you imagine the gall of these people to think by attacking us because we asked for land back was going to win?

When we crossed the border fighting had already started, and we were assigned to protect a Panzer unit against aircraft. Our pilots destroyed much of the Polish air force so they only had limited attacks they could make. I was on a 2cm Flak 30 then.

We used this on ground targets as well, the Poles were good at trying to hide and attack us from behind. They were able to cut us off once and we had to swing around to prevent encirclement. That was my first action, and I was quite scared I remember.

They attacked us with those small tanks and armored cars.

We pelted them with fire, and one of our rounds disabled a scout car where they all jumped out and ran. We passed by a column of what appeared to be surrendered soldiers with a white flag. As we passed by they grabbed weapons out of a cart and opened fire on us.

We took our first casualty from this attack which was not right. It is not correct to hide behind a flag of truce to then attack in a sneaky way. We learned later that they had been encouraged by their leaders to fight us any way they could. They were told we were so much bigger than them that they had to use all means necessary to fight.

I know because of this, some of the soldiers and officers were charged for crimes and sent to camps or shot. We had a big fight with the Poles; it was no push over for us.

They had a well-trained, large army that had modern weapons. We stayed pretty busy until the fighting ended.

Then we set up our unit for occupation duty, and were ever watchful for the western allies. We feared they may land troops but they never did. They also never declared war on Russia when Stalin invaded Poland, but the reason for going to war was to protect Poland. Does that make sense?

The people were welcoming to us, we even saw Jews in Poland living in their tight communities. They looked so poor and devilish yet they all had gold and silver hidden away and made much money on selling scrap and used things. We also heard of reports of them being attacked by the Poles too. The Poles linked the Jews to us, and accused them of being German allies.

Can you imagine that? They even carried out organized attacks on them in some areas down south. I was told many Jews were killed there, and it was loose Polish militias that went crazy until order was restored by German units. We mingled with the people and those who spoke German would come to speak to us.

We even had to help the people rebuild as well. If anything had been destroyed by war, even by the Polish army, we helped them repair it. In this we did use Jews to help, they were put in a gang by us and helped patch holes in the brick roads. They were paid, but they complained it was not enough I remember. They always wanted to get the best deal.

[Above: In Crete, a Luftwaffe officer stands with the Flak-Regiment 23. Click to enlarge.]

You said you fought in France. Can I ask how that was and what did you see?

Herbert: Yes sir, now something I must tell you is that early units of the war were often moved and transferred and changed. I found myself back in Germany after Poland and then moved right into the west front. We attacked France and Belgium in May of 1940 I remember.

You see France declared war on us and then we invaded them in May to force an end to the war. It was Rommel and Guderian who smashed the French and broke through. We had a busy time of it as now we faced not only the large French air force but the RAF [British Royal Air Force]. They had better planes and would come down to attack us.

We had to use the Flak to defend important ground areas like bridges or supply areas. We would often be thrown into ground action as well. I had been awarded the Iron Cross here in France for the successful defense of a bridge crossing. No sooner had we had a good action against the enemy when I was called back to Germany for further training and to go to NCO school. I never really was able to enjoy that summer in France. I had to hear from comrades about how nice it was.

What was your next action?

Herbert: Well I will tell you, I was promoted to Unteroffizier of the Flak artillery. We wore the red piping on our collars. This was in the end of 1940 and then I was moved south for the action in Yugoslavia. In April I think, of 1941, the British had landed in Greece and Mussolini and his soldiers were in trouble.

There was a revolt or something and we were asked to come into Yugoslavia to keep the British out. Hitler decided to go all out and to take the whole area, including Greece. So we went into the Balkans and it was like a spring holiday. If I remember there was very little fighting.

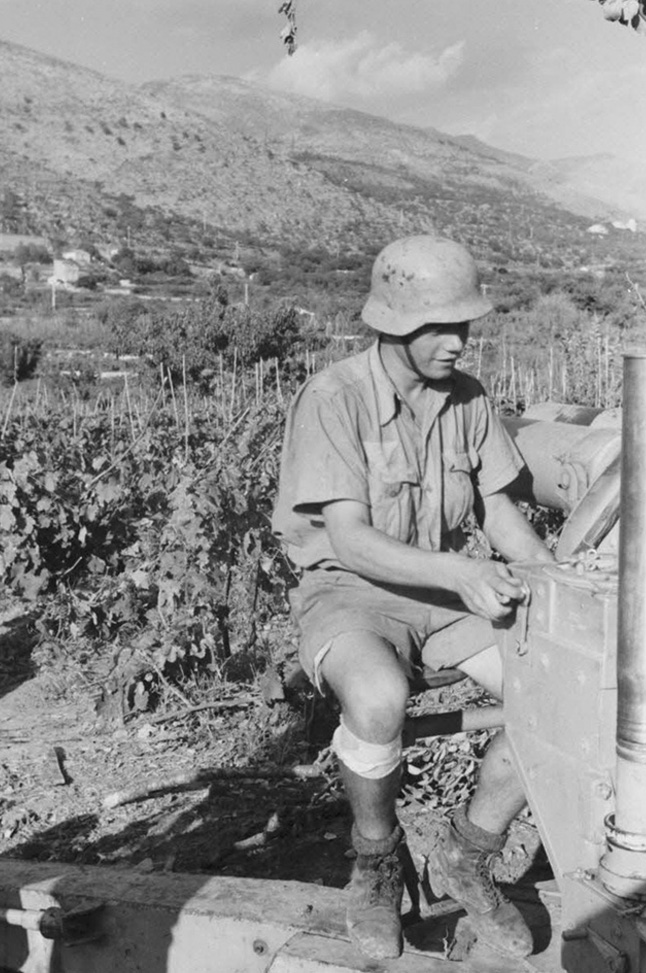

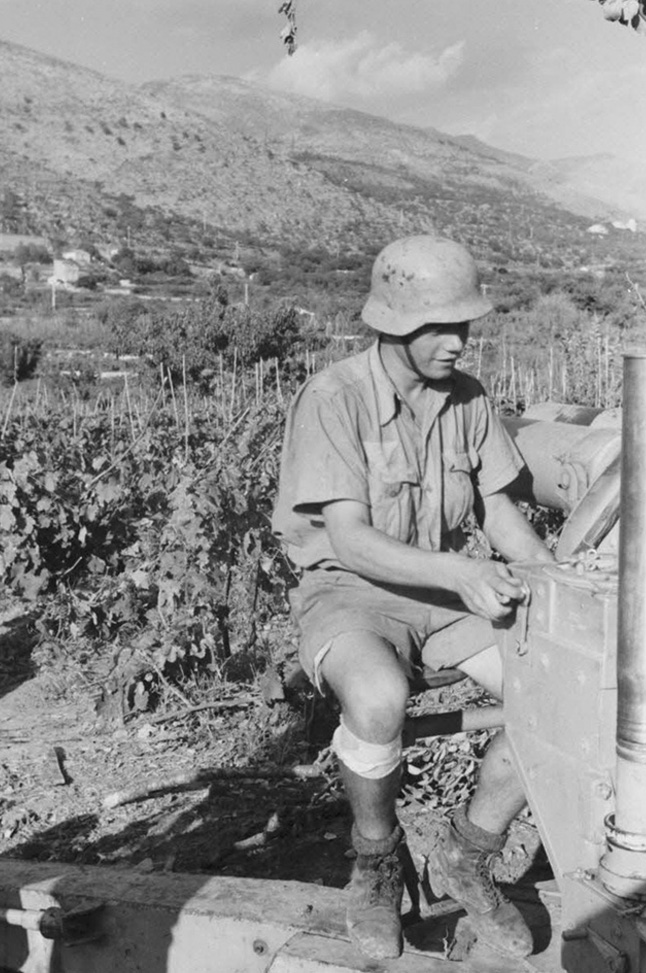

We settled into occupation duty and guarded against low level air attacks. That May there was the paratroop landings on Crete, you know of this place? Once it was taken I was moved there for occupation duties. It was rumored we would move on to Africa to help Rommel but we never did.

Can I ask how life on Crete was since you were there on occupation duty? How did the civilians treat you?

Herbert: I came to Crete right after the final fighting but there was a fear the British would return. We had to be watchful as the people mostly were friendly, but the British had many agents working for them. They were convinced that if they resisted us the British would come back.

Many of these people were arrested and sent to prison to make sure they could not make trouble. My unit's batteries were assigned to the airfield at Maleme [a small village and military airport in north western Crete] and the surrounding areas. It was nice there; the weather was warm and sunny almost every day. We were by the beach so we could go swim and get some sun on days off. While I was there I saw little action, only perhaps a raid or two by the British or their agents.

German soldiers would be seen mingling with Cretans and some even had women friends who would keep them company. The priests blessed us and would offer services to any faithful. It was a good time for me, I felt good, looked good with a tan, and enjoyed it all.

Now remember when the attack on Crete happened there had been issues with some of the civilians being accused of killing wounded paratroopers and so forth.

Because of this there were harsh reprisals that took place to punish anyone who took part in this. This was not popular and I know some of the people did not like us being there, so not everyone was happy to live with us.

There were small acts of sabotage and I know some agents were arrested at times, some were even shot as spies, as is common in any war. The general in charge was [Bruno] Bräuer, and he was very humane to the people, even when attacks were made on phone or power lines, he told us not everyone is our enemy.

He was killed after the war for crimes here, but I never saw any of this, it seemed to me that we were very restrained and kind to the Cretans. All I ever saw was either indifference to us or cooperation. I do not think he, or any Germans here, deserved their fate.

The only times I ever saw any issues was in 1943, we had to seize Italian islands by Crete, and the civilian agents worked with the British to try to disable boats and slash tires of trucks. Of course anyone caught in the act was tried and sentenced to death, and it was mostly carried out unless there were other circumstances.

I know of a few German soldiers who were killed while I was there. One was a big deal where a comrade got a married woman pregnant, and her husband found out and killed her and the soldier after finding out. He was tried by German and Greek authorities and executed by a joint squad of Greeks and Germans. We had to attend this as a lesson to not have unlawful relationships with married women.

One other issue that I remember was a young soldier who had to be no more than 18. He had taken a liking to a local girl and her boyfriend and his compatriots beat this soldier to where he later died. All involved were caught but were tried by Greek and civilians who pronounced the death sentence. They were all taken away to be shot.

That was the worst I saw on Crete. In spite of small attacks like this Bräuer let many prisoners out as a sign of good will, and we would help the people with harvest and trade them food for olive oils and Cretan specialties. We also attended the many festivals and dances the people would put on. As I say not everyone welcomed us but we managed to have a good coexistence.

I was there until being transferred to the East Front in late 1943. That was a shock to my senses. I went from very hot to wet and cold.

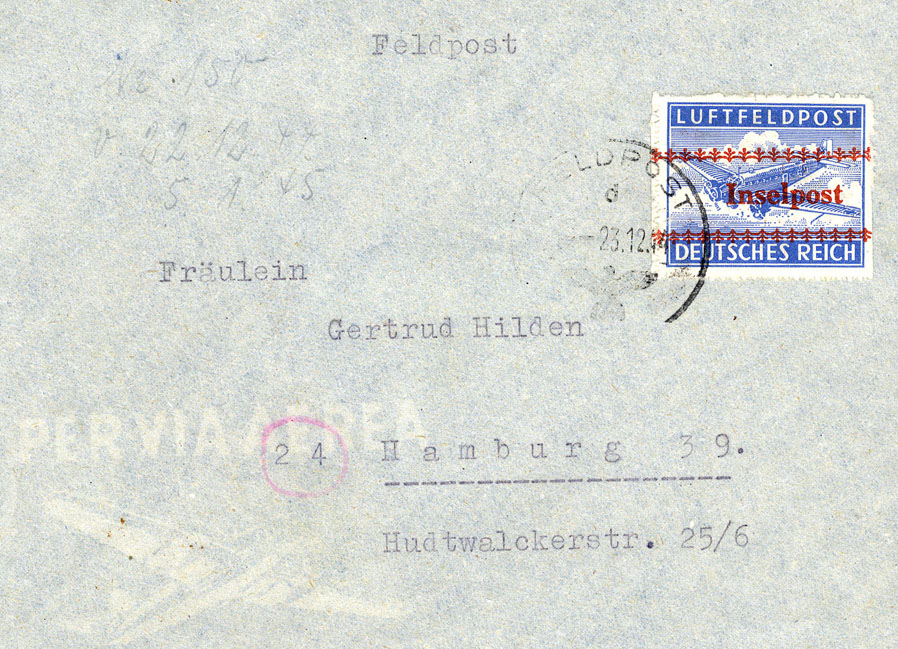

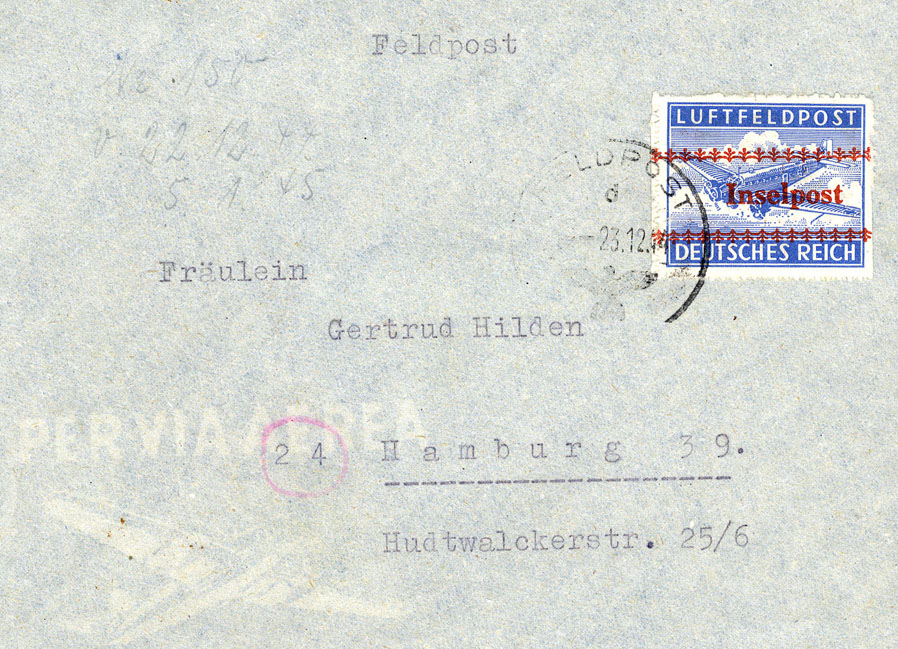

[Above: This is a German feldpost from the occupation of Crete. The postage stamp is a normal feldpost airmail, except it has been overprinted locally with the words 'Inselpost' (Islandpost) on November 1944.]

[Above: Here is a philatelic postcard showing the majority of different Inselpost stamps (Krete, Rhodes and Leros). This uses an Italian Rhodes postcard, which was probably left over when Italy surrrendered to the Allies and the Germans occupied what the Italians had previously occupied. Some of these stamps are very rare just by themselves and on a non-philatelic postcard or envelope would be very pricey.]

Can I ask what it was like in Russia? What do you remember about the fighting and how did the people seem to be treated? Did they seem afraid of Germans?

Herbert: Oh the east was cold and wet which was quite uncomfortable. I was assigned to a mobile gun where we had to follow the Panzers to give them protection. Russia had small villages that were placed far apart; it was truly a vast land. We had to go fight Stalin's army there and it was a hard struggle. The Russians had a very large army and by the end of 1943 was beginning to overpower German forces.

The red air force was large and well equipped; they were a force to be reckoned with for sure. We were often covering Panzer workshops from air attack. I saw some of our allies here as well; they spoke their languages but wore German uniforms. They would come to ask us for things and it was funny to try to communicate with each other.

They said we had three main enemies in Russia, the weather, bugs, and mud. Of course the Soviets would be the top of the list, but it was meant to be soldier's humor. There were also partisans whom were able to get control of large areas and wage a war of their own. I have heard this fight was very cruel and brutal, we were left out of that side thank goodness.

In my time in the east I did not hear of any attacks, but again any accident, derailment, or line down was blamed on them, and it may not have been them doing anything. They did tie up some of the police units and militias that were formed to stop them, but the frontline never had to deal with this threat that I saw.

I was lightly wounded in December of 1943 and sent to Minsk while a Soviet offensive was going on. I was pulled from the hospital and put on light duty guarding the rail hub with a quad barrel flak gun. I thought it strange as the city looked peaceful with not a lot of signs of war.

There were outdoor fairs and concerts that were being held, and it helped take our minds off it all. I saw a Cossack wedding here that seemed out of place in wartime, the pretty young ladies danced with the soldiers and with a precision I had not seen before. They wore very attractive dresses that made us soldiers yearn for the company of a woman. I can tell you now I was homesick for a special female friend back home.

I even met some soldiers of the Waffen-SS here and when I told them I used to wear the black uniform they wanted to know why I did not join them. I told them I enjoyed the Luftwaffe and the SS did not have planes. Today I count myself lucky I did not go that way, many SS men had it very bad after the war.

I must tell you from my time in Russia, and the limited time I saw any fighting, there was no talk of crimes. I understand the SS is said to have done very bad things to the civilians but I never saw anything of the sort, and they certainly did not ever bring it up. I used to be one of them so you would think if they were killing Jews and civilians they would brag.

I heard the opposite after the war. I remember an SS comrade telling about an encounter he had with civilians. Soviet commissars had ordered local civilians to take up arms to fight in 1941. When attacked by an SS assault squad they quickly threw weapons away and gave up, begging to be spared. They were told Germans would shoot all of their families if caught.

They were all taken to the rear as prisoners, but when it was seen they were forced to do this, and they were all farmers who were needed for the harvest, they were let go with a sworn pledge not to resist any German soldier again. This comrade swore this was true and that they never mistreated any prisoners or civilians.

[Above: A beautiful trumpet banner of the Flak-Regiment 23. Click to enlarge.]

I have read and heard that the Germans did wage a ruthless war in the east where millions were killed in cold blood or by extermination. So you never saw any of this?

Herbert: As I have said, I did not, so please stop asking this, you can get one in hot water for speaking about these things. I can tell you again that I never saw anyone being mistreated by German forces. All I saw were times when criminal acts and murderers were punished. The main weapon of the partisan agents was terror, and German units had to be hard in their punishments.

German units were not kind to them, I understand, but I never saw any of the mistreatment they say happened. It is said that the winner gets to tell the story, and I believe this is what happened after the war. They won so they get to tell it their way. If they say crimes happened, you must accept that and not offer any counter argument.

Today it is against the law to downplay anything that our former enemies say happened. Something I will share with you that I noticed back then but I have not shared. In the camps and prison camps prisoners did not often commit suicide I have read. That tells me the conditions were not that bad and they had something to live for.

Now take the Allied camps for us after the war, I was in them and can say they were not good. The suicide rate for German prisoners was high; in the camp I was in I know some of the soldiers ended their lives. They did this as they had nothing to live for; the conditions were bad and there was no prospect of getting out. I am told this happened in many Allied and Soviet camps, yet you hear nothing of it today.

They only seem to say we had it coming if anyone asks about the treatment and deaths of Germans after the war. I have seen reds say we got what we deserved. It was a crime how we were treated and held after the end of the war.

I understand you were part of the Normandy invasion front; can you describe what it was like? How did you feel about the defenses? Again I would like to ask about the civilians and how you saw them treated.

Herbert: Yes I was sent back to France to a new unit, I believe it was in March of 1944. We were placed close to Abbeville [northern France] which had an air base close by. We were on watch for Allied planes and any landings. I remember this area was very quiet for me, and after the east I needed this.

The people were quite friendly, of course again we were the unwelcome quests, but they did not show any hate. We would go to the chicken and dairy farms and barter or buy milk, eggs, and butter. The French were very well known for their cooking and so if you were lucky you would be by a friendly home who would invite you in.

We either stayed on bases, camps, or were billeted with civilians. The later was quite rare as we could only do this on orders or if a family invited us in. With the war still going not many families wanted military on their property as they became a target.

I can tell you I saw a spat with a farmer who was quite upset a radar unit was placed on his hill, among his cows. He was wanting to be paid for any cow killed through enemy attacks. I would hear that almost every day he complained we were on his property, and he really loved it when quad flak was placed there.

As for the defense, I remember reading about this after the war, and I observed the findings myself while there. All along the coast, and it was a long coastline, we were understrength. Rommel was a good general, but he had too little to work with. Where the Allies landed in Normandy, there were foreign troops from eastern legions who did not want to be there. The fortifications were only a few smaller pillboxes and batteries, nothing strong enough to fight even one battleship.

There were no real Panzer forces by the beaches, only outdated French tanks. The Luftwaffe had been bled dry in the west. There were large gaps in the defenses, and it made it very easy for the Allies to just walk ashore in many areas and establish a beach head. The Americans probably had it the worst, as they had some high ground that aided the defense and caused a bottle neck effect which took concentrated fire.

Remember, the Allies established a vast bridgehead in just a few hours, moving several kilometers in places. That is testament that the defenses were non-existent in some areas. We could hear all the sounds of battle that day, and we had air attacks to fight off. My battery accounted for shooting down one bomber and two fighters in the first few days of the invasion.

We were not moved into the actual battle area until a few days later, and it was hard going. The Allies attacked everything on the roads. When moving through these small villages I was surprised at the destruction brought by the Allies there. There were plenty of French who supported us I must tell you.

They resented the way the Allies recklessly bombed their towns, and many civilians were killed in either strafing attacks or bombardments. You never hear of this however, but I know it happened as I saw it. They would quietly come out and offer us a drink, or a bite to eat. I saw our medical teams work with the French Red Cross and doctors treating civilians.

In the area of Normandy we set in a defense and tried to drive off the Allied air fleets. We had luck on a few days where we got very good at luring in the fighter bombers and then letting loose with a wall of flak. We shot down a few of the P47 planes and British types like the Hurricane and Typhoon.

We once brought an American down right by our position and the pilot was unable to get out, the soldiers buried him with military honors. It did not give me a good feeling to know we took a life, but in war you don't think, you just act. All of this was in vain, however, because our lines broke and we had to retreat from Normandy.

My unit had to watch the skies as what could be saved was moved away from the front under the noses of the Allies. We had a hard time being supplied and had to save our shells. I was lucky as I had been able to get out of France without a scratch, it was here I think we realized the war was lost.

How did the war end for you?

Herbert: Ah, the ending. I was send back to Germany to rest and rebuild our unit. From there I was ordered back to the east in a new motorized flak unit. I was now promoted again to a senior sergeant. I was assigned command of a 20mm Flak on an armored truck (Sd.Kfz.10/5). This gave better protection and had a better gun.

We were sent to defend the Hungarians as the Russians had broken the front and were moving west very fast. After training and rest I went into action in Hungary and was tasked with defending rail heads so reinforcements and supplies could be brought in.

For us here, the red air force was not very active, we had raids by the Allies we fought off, and later the Soviets came. In 1945 there was a big offensive to try to take back lost territory and drive the Soviets back.

It was all lost then, we had no fuel, ammunition was low, and our morale was in a bad state. Many men just gave up; they had no more in them. I remember by April we had been pushed back into the Reich borders, and I was hearing the Soviets were doing very bad things.

I can tell you I saw some of this. When they talk of war crimes by Germans, I can't help but think there is a mistaken identity. I saw comrades who had surrendered but were executed by a shot in the back of the head with their hands tied. In Hungary I saw a village that was taken back and there were civilians who had been killed who appeared to be shot in the head as well.

We could not do anything for them, but I wondered what they could have done to deserve that fate. I learned later that Soviet soldiers were encouraged to do these things, based on lies of their propaganda which told fanciful stories meant to inflame them. This caused them to act out of extreme hatred towards anyone they saw as their enemies.

I had made up my mind I would get away from the east and find the Allies, it was said they were humane. As our units began disintegrating in the last month we set off for the west. No sooner did we start moving that we were surprised by a Russian cavalry unit with partisans.

To my surprise they acted somewhat humanely.

They took us prisoner, and in broken German said we would be marched to the Russian lines to surrender and then be released as we were not SS. So we all agreed and did what we were told. They made us march all night until we came to their lines.

From there I was processed and sent to an outdoor holding camp. Something strange happened though; a man came to the woods late at night and spoke to soldiers as best he could. He said the Russians were not letting anyone go as promised. Without drawing attention to this we listened to him tell us of a way to get to the Americans.

We spoke about this and some wanted to try their luck and others were just too done with it all, they trusted in their fate. I was one who wanted to get away. After the surrender they announced we were going to be moved and that trucks would come and take us to be processed.

When asked why we were not just let go from here, a soldier let the truth out, saying why would criminals get to leave after a crime. He was a German who was a communist and defected to Stalin. He showed contempt to us and would hit us with his rifle often. I knew then I had to get away as that was my clue that something was wrong.

A night later there was a terrible storm, and we knew it was now the time. It was gusty rain and perfect to hide our movements, we went to the fence, crawled under and ran for our lives. The guards were in their shelters and had no desire to be out in lightning. They had no idea we fled, it seemed, but we ran for as long as we could.

We knew not to stop and to stick to the woods. That morning it stopped raining and we stayed in the woods avoiding any towns. We kept this up until a few days later when we came to a check point and saw new uniforms of the Americans by the Czech border. We walked up to them and surrendered saying we had been left on our own from the south and wanted the war to be over.

They took us away and put us all in a camp where it was not clean, and we had very little food there. Some of the men had gotten sick and it appeared the Americans did not really help them. I felt like I had gone from bad to worse with American indifference. But as soon as I had lost faith in it all, they all of a sudden seemed to have had a change of heart around July.

Yes, I think it was in July of 1945, we received food, medical care, and best of all were moved to shelters. We were in better spirits now and were allowed to go in work details helping the Americans with restoring things. I was allowed to work on motorbikes so civilians could travel. They even started paying us for the work, and that December I was allowed to go home for Christmas. So for me the war was finally done.

[Above: In Crete, the gunners of the 'A' gun of the 3rd battery of the Flak-Regiment 23 wait with their 8,8 cm flak gun. Click to enlarge.]

[Above: In Crete, technicians and gunners of the Flak-Regiment 23 ready their machines for battle. Click to enlarge.]

Back to Interviews