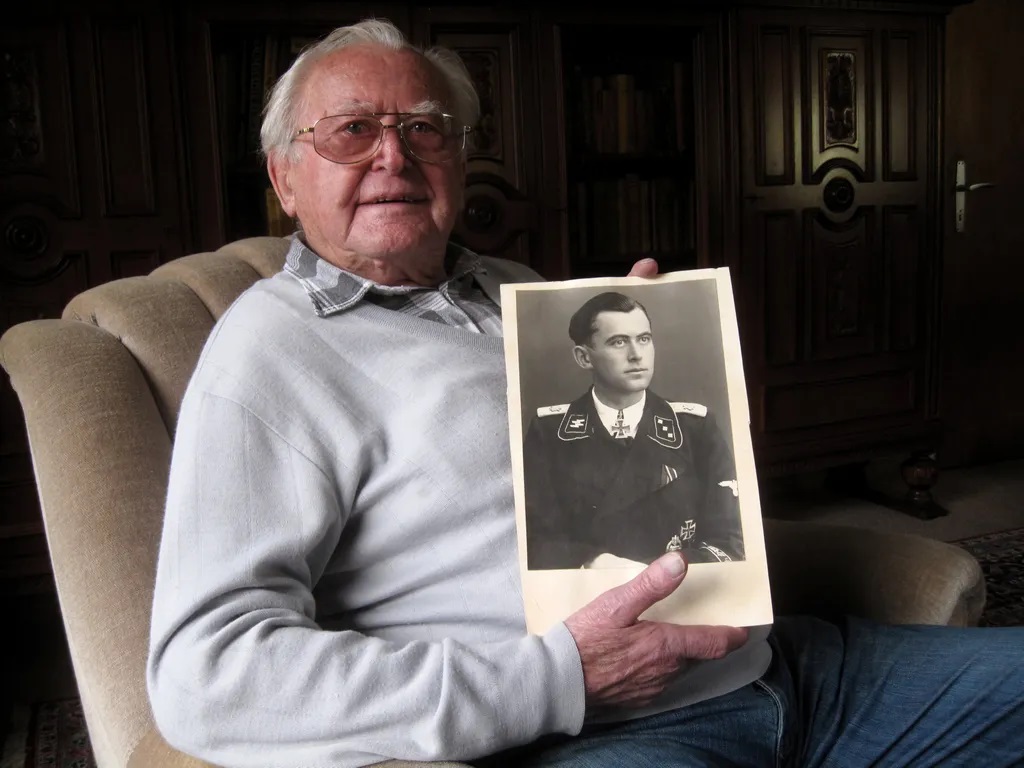

Interview with Knight's Cross winner SS-Oberscharführer Kurt Sametreiter of the 1. SS-Panzerdivision 'Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler', Fuschl, Austria, 1989.

Interview with Knight's Cross winner SS-Oberscharführer Kurt Sametreiter of the 1. SS-Panzerdivision 'Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler', Fuschl, Austria, 1989.

Kurt: A little history first, I was born in 1922 in the Austrian Alps and my

father worked for the railroad, building tunnels. We grew up with not a lot of

money, but always found a way to stay fed. I got lucky and was picked to be

a ball boy at a tennis club, so that helped. In 1938 Austria decided to join

with Germany, which almost all Austrians supported. Hitler revived

Germany again and we knew he would do the same for us, our economy was

not good under our current leaders.

So how did I come to the SS? One of the first things to happen was

recruitment for the German Wehrmacht and SS. I was an adventurous spirit

and was impressed by the recruiting literature that the SS handed out. The SS

was a very hard branch to get into and I was afraid they would not take me,

as many boys in my area were turned away. They were known to be an elite

group of men, the best of the best.

To my surprise I was accepted and told I needed to be fattened up

a bit, as I was undernourished. This started my adventure. I was on a train to

Dachau to the new SS barracks, which still had that fresh paint and wood

smell. I was accepted in the SS-Totenkopf Standarte 1 'Oberbayern'.

Dachau was a concentration camp, did you see the prisoners or have any

interaction with them?

Kurt: Yes, the prisoners were assigned work details around the area to clean

and maintain the barracks. We would oftentimes work alongside them to do

details. We had to clean the steps and mop daily to make sure the barracks

were ready for inspection at any time. We were told not to give the prisoners

anything, but many would share cigarettes and tobacco. I never saw any

abuse or mistreatment of anyone. No prisoners ever complained to us about

their treatment.

I saw quite the opposite; prisoners seemed very relaxed and happy.

There would be celebrations in the camp when a prisoner was due to be

released, the commander even allowed them to have alcohol, although it was

a very small portion. We were jealous, as we were not allowed any, since we

were in training. I find the photos and stories shown after the war hard to believe, the prisoners seemed very well taken care of and were not bothered

in any way, many even roamed free to do their details.

What was your training like?

Kurt: It started out easy, with learning to march, lots of exercise like running

and relays, and inspections. Later on it moved to training with weapons, first

pistols, then the K98 rifle, then machine guns. I remember one time a recruit

was watching a group of women workers and the instructor saw him, he ran

up to him and told him since he did not want to participate with us, to go with

the women. He did that and their leader made him march back to us, and then

run around the barracks three times. He learned to pay attention after this.

One thing I want to mention is how different the SS was compared

to the army; our officers trained with us and did the same tasks as us. This

way it showed they were part of us and could do our same tasks. The SS had

leadership, but no class structure of officer versus enlisted. We were all in

this thing together, which paid off on the field of battle; we were trained to

work as a united team.

As newly minted recruits, we were chosen to participate in the 1938

party congress, which was a huge honor. My only gripe was it was very hot

in our new black uniforms, with full kit; I sweated like crazy. We had special

training by doctors on how to stay at attention, or parade rest [a formal position assumed by a soldier in ranks in which he remains silent and motionless...] without passing

out. There were water stands everywhere to keep everyone hydrated, there

were tens of thousands of participants on each day.

Some even got into the many lakes surrounding the area. Nuremberg

was a great town with very friendly inhabitants. We had a camp set up and

invited many of the girls to drinks and dancing. Our officers stayed right with

us and drank and danced like everyone else. After this was over, I was

transferred to a Panzerjäger company where I learned to use the Pak36 gun and learned tactics to hunt tanks.

[Above: A gorgeous rendition of a Liebstandarte knight by battlefield artist SS-Oberscharführer Ernst Krause. Click to enlarge.]

You mentioned you were part of the union with Czechoslovakia, how did the

people view you?

Kurt: Yes, my unit was part of the German force to move into the area. The

people largely welcomed us, there was no shooting, we had been instructed

to make a good impression and to not make the people feel like we occupied

them. We had recruiters with us, who set about trying to recruit from the

Czech army and civilians. Many of the civilians brought us water and treats,

which was welcomed; these were called 'flower campaigns', as we wanted to

win the hearts of the people, not to conquer them.

This was a short-lived action, we stayed in barracks and worked

with the army to ensure a smooth transfer of authority. We mainly went out

and spoke with people to show them we were here as friends. Warmongers

had told the people we were here for a fight, and nothing was further from

the truth. A new leader took command and was pro-German [Emil Hácha (July 12, 1872 – June 27, 1945)], the people

responded very well.

You served in Poland with SS-Heimwehr 'Danzig'?

Kurt: Yes, after moving back to Dachau, we did more training and then

received orders to report for a vacation up north. We were on a big cruise

ship and enjoyed all the amenities. Once we were by Danzig all the fun

stopped and we had to go back to military drills and shooting exercises. The

day the war began we joined other Danzig units and occupied key offices.

Most Poles wanted nothing to do with the war.

Some of the war lovers had secretly fortified buildings and stashed

weapons for an uprising. The Polish plan was to make Danzig Polish; they

had tried to push the German majority out by putting Poles in key positions to

help an uprising. Our men had small problems getting them out of the post

office; they also had fortified Westerplatte [a peninsula located on the Baltic Sea], which was against the treaty.

I briefly was part of the home defense to take this island.

The Poles

were dug in and had cannon, machine guns, and mortars. We only had rifles,

pistols, and a few light machine guns. The Luftwaffe had to help to break down the

strong bunkers. Even having a battle cruiser did not help that much, but when

they surrendered, they were treated very well even though they fought a

senseless battle and caused needless loses.

My unit also had sporadic fights into Poland, guarding a bridge so

it would not be destroyed, and rounding up the scattered Polish forces who

refused to surrender earlier. These men proved to be quite nasty and fought

more like bandits than soldiers. I will say that the Polish people had no taste

for war, and either stayed in their homes, or at best came out to watch us. The

German minority was very happy to see us and greeted us as liberators

bringing us flowers, food and drink.

After the Polish campaign, we were joined into the 'Totenkopf'

Division and received cuff titles. We met with our NCOs and officers and

they covered our performance in battle and graded each of us. I received good

marks, but not high. We were still very green.

You then fought in France, what happened and how were your relations with

the civilians?

Kurt: Yes, 'Totenkopf' was involved as a reserve division; we entered through

Holland, then Belgium, and finally France. We didn't see any action until we

met the English and French at Arras [France]. The English tore through our lightly

defended lines. Rommel had the idea of using flak guns to stop them as our

Pak36 were useless against the heavier armor. Rounds just bounced off,

one could see this, and it was unnerving.

The English gave us a fight, we had many new, young recruits and

they broke easy, or ran away. I saw my first English prisoners and met with

them to talk about the war, and share photos of home. I found them to be very

proper and just like us; we said it was a shame to meet this way. This battle

also had a dark side to it as well. We saw evidence of civilians who had been

shot down, we were told they were German sympathizers and shot by their

own army. Rumor spread too that wounded German pilots had been

executed and murdered by civilians. Parts of the infantry regiment was fired

on by reversed bullets [a German anti-tank method for penetrating armor] and suffered needless wounds, which cause painful

deaths. The English had some fanatics who really believed in the war and

winning any way they could; so is the curse of war.

These instances cause a reaction that was unfortunate; the 'Totenkopf'

Division is accused of killing prisoners, civilians, and African soldiers. I know

some French women claimed African soldiers raped them, so any guilty man

was executed. French police were brought in to help investigate. It was said

two young soldiers shot down English prisoners, but no one I knew saw this

personally, it was not known until after the war, so I am skeptical. Some

civilians were executed for crimes and were tried by French helpers.

For the most part the civilians behaved, just like in Poland, and only

came out if they needed our help or were just curious. One of our doctors helped a

child, and we went out of our way to keep civilians away from our columns,

so they would not be strafed. Luckily our Luftwaffe controlled the skies most

days. We pushed the English back to Dunkirk and then received orders to

halt. We were puzzled by this, rumors were everywhere that the Führer

wanted them to just leave, Göring wanted the Luftwaffe to get credit, or the

general staff lost its nerves. Today it is safe to say the Führer was extending

an olive branch.

We were moved down south by Spain when word of the surrender

was received, we celebrated. During the stay I was transferred to the LAH [Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler] since I had tank hunting training and they were building into a division. I was

sent to Metz, just in time to start more training and was greeted by Sepp

Dietrich.

[Above: Kurt Sametreiter.]

You said you fought with the LAH in the Balkans?

Kurt: This campaign was quick for the division. We did not see much fighting

until we hit the Klidi Pass [Battle of Vevi in Greece], then the English put up a fight. They made stands

on the tight roads, but we became good at enveloping them. We had learned

to become better shots and knocked out their vehicles and strong points with

ease. I saw many prisoners, and we allowed them to ride with us while we

talked about home and girlfriends. We went out of our way to take them

prisoner, often times at our own peril. We viewed them as brothers; the

Greeks welcomed us as friends, not as enemies.

What was the war with Russia like and why did Germany attack?

Kurt: The last part first, history is not always correct, especially when

dishonest people write the history. Russia was very clear it wanted a world

revolution and demonstrated it would use force to enforce this plan. The

Führer used politics to keep Russia at bay, but it was going to come to war

at some point. We attacked them before they attacked us, it is evident to me

due to the vast amount of men and material we captured. I saw the huge

stockpiles of ammunition, equipment, and aircraft. We even took maps off

prisoners detailing routes through west Poland and the Reich. Germany made a

defensive attack to break up a planned attack on us; our aim was to save

Europe from Bolshevism, not to take living space.

The LAH went into Russia not a full division, and the going was

tough, we lacked fuel and ammunition, which angered our leaders. Orders

were sent out to conserve everything. This is where some men started using

captured Russian weapons, as there was plenty of ammo. I remember it was

hot and dusty; the roads were not like Europe, they were full of ruts, which

slowed us down. We were miserable, then winter hit.

It might surprise you to know that the vast majority of Russians

welcomed us as their liberators. They hated Stalin and the regime that ruled

over them. The LAH came upon prisons where the NKVD had shot all the

inmates who were political. That winter the Russians put the whole front into

retreat due to massive counter-attacks. It was during the winter that my unit

was upgraded with mounted anti-tank guns, and we had immediate success.

We were sent to France in the summer and had a large parade with

throngs of people watching. At this time, we were built into a full armored

division, and put on alert against Allied landings. We trained on our new

weapons and felt very confident we could take on superior tanks. We had

gained a lot confidence fighting, and were seen as a very mobile, elite

division. The LAH ended up back on the Eastern Front just in time for

Kharkov. It was here my gun was hit after knocking out Russian tanks, I was the only survivor, and luck favored me as I was in an open area, but I was

wounded and sent home to recover.

How did you win the Knight's Cross?

Kurt: It was during Kursk, I was still with the tank hunter battalion. I had a

very good crew, and in one day we knocked out 24 tanks. They attacked our

small force with 40 tanks. It was a blood bath for the Russians; we mowed

them down and suffered very few losses. This was the battle of Kursk, we

could have won this, as we had penetrated deeply into their lines, and we

were forcing their reserves to be committed. The field was littered with

Russian tanks, not German. They outnumbered us heavily, but we were better

shots. They knew we were coming, and still could not stop us.

The Führer had traitors who were advising him and talked him into

withdrawing when victory was close. We were pulled out and sent to Italy to

disarm the Italians. However, I was sent home due to being awarded the Knight's Cross.

I got to see my parents, and gifts came in from all over. I met our Gauleiter,

as was customary, but I wanted to stay at home to see friends and family. I

was in the newspapers, which I thought was too much, everyone wanted to

hear about our battles, which I did not want to talk about. I then had to hurry

to meet my regiment in Italy and got into some trouble along the way by

having too much fun; I was put under a curfew for a few days while others

mingled with Italian girls. We had a good relationship with the people

wherever we went, lots of dinners, dances, and parties, when we could.

[Above: Noble knights of the Liebstandarte SS Adolf Hitler guarding a recruiting office.]

So you believe Germany could have won Kursk?

Kurt: Yes I do, our Korps had pushed deep into the Russian defenses, and

had knocked out much of their armor, while ours was mostly intact. Our kill

ratios were ridiculous; I have heard that for every German Panzer lost, 15

Russian tanks were lost. From the view of the battlefield, I would believe

this. We had very few Tigers, Panthers, or heavy Panzer IVs but this small

force, along with the anti-tank units, terrorized the Russians. We took many

prisoners who seemed at their rope's end, utterly exhausted.

What about all the claims of war crimes committed by the LAH and Waffen-SS in general?

Kurt: I cannot speak for other divisions, but the LAH will stand blameless.

War is a dirty affair, and it is easy to be caught up with rage. Some soldiers

can witness cruelty and then become cruel themselves. I saw this once through binoculars; Russian soldiers were seen shooting a peasant family

who allowed Germans to stay in a barn. The hamlet was attacked and

captured, and as soon as the Russian platoon surrendered, they were all shot

down since they killed the civilians.

This is the legacy of the German conduct of the war; we were at the

receiving end of very cruel deeds by our enemies, and when we in turn

responded, the victors turned these into war crimes. I suspect it was the same

for every accused German unit, a reaction to an action that was justified under

German or international law, but the victors changed the laws in order to

prosecute our men but shield themselves for the very same acts.

I will share with you an example of how our relations with civilians

went. My [motorized] gun accidently ran over a horse, the owner was not paying

attention, and trying to hog the road. We were disciplined for hitting the

horse, we had to pay out of pocket to buy a better horse and apologize.

Another example: one of our men stole two eggs and received punishment

and had to pay the equivalent of a dozen eggs to the farmer. He had no money,

so he had to give the farmer a watch he bought in Paris.

My point is, we had very strict orders to treat civilians with respect

and good will. Many German men had sexual relations with the women of

other countries, I looked down on this as many were married, and it went

against how we were taught to behave, but I suppose the stress of battle had

to be tamed.

What was the end of the war like for you?

Kurt: I was transferred to 'Nederland' and used in the east as a rear-guard force and we

caused the Russians losses. We kept retreating until we came to the

Americans who took us prisoner. A Jewish officer who was surprisingly nice

to me, interrogated me. He knew I was an SS officer and put me to work as a

mechanic in the motor pool. So many of my comrades were not treated this

way and were persecuted after the war. Even the black soldiers were kind to

me and left me with a good impression. I was a very lucky one, but others in

my family were not. I know many women who were raped, and the men sent

away for the smallest infractions. Being a party member was certain death if

the partisans or Russians got you.

[Above: Kurt Sametreiter.]

Kurt Sametreiter's Knight's Cross recommendation:

'On the 11.07.1943, SS-Oberscharführer Sametreiter was with his Zug and the II./SS-Pz.Gren.Rgt. 1 LSSAH in the attack on Swch. Stalinks and forest located south of there. During a night battle they threw the enemy out of Sowchose.

On the 12.07.1943 at 06:30 hours the enemy advanced out of Jamki and Storostrowoje with around 40 tanks and supporting infantry, and these counter attacked Sowchose Stalinks and Hill 245.9. SS-Oberscharführer and Zugführer Sametreiter, with 4 of his self-propelled 7.5cm guns, was able to prevent an enemy breakthrough through his determined leadership. Making his own decision, Sametreiter went with his Platoon past our outermost infantry line and out towards the enemy tanks, continuously shooting at them for over an hour. In the end he and his platoon destroyed a total of 24 enemy tanks. All of his Platoon then shot at the enemy infantry with their high-explosive rounds and this caused them to retreat.

After they had fired all of their shells, he gave the order for his vehicles to drive against the enemy infantry and give further cover to our own men. It is due to his determined leadership that the tank attack was defeated. The Platoon of Sametreiter gave combat covering fire to the men.'

[Above: Kurt Sametreiter, the old warrior, long in his years.]

[Above: Kurt Sametreiter.]