Interview with Knight's Cross holder and Sturmgeschütz [assault gun] officer Eberhard 'Hardy' Schmalz, USA, 1998.

[Above: Eberhard Schmalz.]

Interview with Knight's Cross holder and Sturmgeschütz [assault gun] officer Eberhard 'Hardy' Schmalz, USA, 1998.

[Above: Eberhard Schmalz.]

Thanks for agreeing to meet to talk to me; we have discussed your life during the Third Reich so I would like to take down some of your memories. What brought you to join the army?

Hardy: Well young man, I was a member of the Hitler Youth and they instill a deep respect for the military. We attended a parade in which the Panzer arm was in and I was deeply impressed with the esprit de corps of this group. I decided, when my two years of service came, I would join the Panzers. It did not work out the way I planned. I enlisted in 1938 as a motorcycle rider to deliver messages, in an anti-tank unit.

In Germany at this time all young men had to serve six months in the RAD [Reichsarbeitsdienst (Reichs Labor Service)] to get a feel for manual work, either building state projects or environmental reclamation. After this, you were expected to give two years of service to the state in the branch of your choice. I must say they were easy to work with and usually gave one what you asked for. In some instances, however you had to go where they assigned you.

What was your training like?

Hardy: The German army was just like any other army in the world. You applied, went through the recruiting process and medical exams, and then reported to your training battalion's barracks at the time you were given. Our training officers were usually NCOs who had been in the army for a while, some were WWI veterans. They were tough on us, always repeating, "You can do it right or do it again."

We would go to bed early and get up early, stand in formation while we did exercises, then run. The army was very focused on keeping us in shape. The food was good and healthy, we had to take vitamins to supplement our diet, and drinking too much was forbidden.

My training started as an infantryman, learning infantry tactics, weapons, and first aid. Early on, the army spent much time on drilling and polishing. As the war went on most training was combat oriented with less and less polish. One day I saw the 3.7cm anti-tank gun, and liked its looks. A soldier told me this was the future of war, guns that could knock out armor. This put the seed in my head that I might like this arm of the Wehrmacht.

I was chosen to be a runner to take messages to HQ staff, and then take them to other units. I was called a Kradmelder, short for motorcycle dispatcher rider, a very important job as a battle could be lost on failure to relay orders.

What do you remember about the declaration of war in September of 1939?

Hardy: I think many Germans had mixed feelings; a sense of disgust that we were at it again, fear of what might come, and bravado that we could finally get even with the Allies. I felt in between. I didn't understand why Hitler took something that was actually going so well for most Germans, and all of a sudden started a war. Studying this more today, I wonder if he was actually forced into something he did not want; evidence is starting to point to this and I was never aware of his peace proposals.

I wanted to go on an adventure; I must say I was young and foolish. I heard on the radio that the British bombed Germany the first day of the war, and France attacked Reich territory, so it was never a phony war. I wanted to get even with this, so I fell into the camp that wanted to right the wrongs of Germany's defeat in the first war, but was fearful we would somehow find a way to involve the whole world again.

One of my many criticisms of how we fought was that you could not tell there was a war on until 1943. We should have geared up to fight with full mobilization and output as soon as the Allies declared war. We wasted prime material on pipe dreams, and tanks that were a waste of time. I always felt that if we focused on Stugs ['Sturmgeschütz', or assault gun], Luftwaffe, and U-boats we perhaps could have overcome Allied superiority with sheer knockout power. Meaning we would have enough forces to execute a 30-to-1 kill ratio as an example.

Instead, we had a few tiny units who did well with big tanks, but they were too few and broke down too often. When they did fight, they could be easily knocked out, as they were slow and cumbersome. I told you I saw the Tiger later on and was not impressed, as it was too big to transport easily, and not suitable for some of the terrain it fought in. These took away any advantage this beast had.

What was it like being a Panzerjäger [tank hunter] on the east front?

Hardy: Well, I cannot say it was a good time or fun. As I mentioned I started as a Kradmelder but had the chance to go to the tank hunters so I went to training that started with the 38(t) chassis with a small 4.7 gun that was ineffective against the better Soviet tanks. It was decided soon after this shock to mount the 7.5 Pak [Pak is the abbreviation for 'Panzerabwehrkanone', or anti-tank gun] and even the Soviet 76mm gun on this chassis, making it very formidable. It was a new invention in warfare, a mobile artillery piece capable of killing tanks, then running away.

I was assigned to a Marder III [the name for a series of German tank destroyers] with the 76mm gun and I was amazed at the range with which it could kill a T34. Once I hit a T34 at such an astonishing range it seemed unreal, the Russian plain was excellent for tank killing at long distances. I loved this platform, it was somewhat comfortable and roomy compared to other armor, and it moved fast and light. The Soviets feared these mighty guns.

I won the German Cross because the Marder was so nimble. We could hide in ambush, fire and be gone before any return fire, moving to fire again. Once, we knocked out several T34s, thwarting a large attack on the Don bridgehead and saving our line. My crew were masters in ambush and camouflage, not to mention repairing this vehicle, which was simple.

What was your impression of the Soviet soldier and the civilians?

Hardy: The Russian soldier was fighting for his home, so he was fanatical and fearless, but at times careless and cowardly. We made the mistake of allowing archenemies to join our ranks and let out their vengeance on whomever they felt wronged them. This played out in the east and Balkans. I saw the aftermath of the cleansing that Ukrainian and Polish forces exacted against what I am sure were innocent Russians in the wrong place at the wrong time.

I never fully understood the intense hatred in these regions of Europe, but it was certainly bloody, with Germany stuck in the middle as we stirred it up. Because these militias many times wore German uniforms, the population assumed it was us who did these things. In the early going of Barbarossa the people welcomed us many times as liberators, when we retreated in 43/44 they viewed us as the enemy more times than not. We did have many supporters however, who shared a hatred of communism.

I personally had very good relations wherever I went; the people were warm and friendly always offering food and shelter, giving what little they had. When my unit would stop in a town, the cooks would be busy as everyone came out with dishes to make and often times we had big dinners in barns or outside, if the weather was good.

I can say we treated Russian prisoners as best we could, when they surrendered we would jump down, search them, and then send them back to our rear areas. I saw many times where our soldiers shared food with them and cared for their wounds. I never saw any cruelty and would not have stood for it. We went so far as to keep Russians as helpers, we called them Hiwis [German abbreviation for 'Hilfswilliger', which translates to 'auxiliary volunteer'] and often times they were prisoners who simply did not want to go to a POW camp. It was strange having former enemies helping, but that is what happened, and I never heard of any of them attacking or sabotaging us.

Many civilians come forward today telling different stories about us, I am not sure whether to believe them or say it has to be Soviet propaganda. I recently learned partisans put on our uniforms to terrorize those who helped us, which perhaps would account for some of the atrocity stories. I never saw Germans act badly towards civilians.

You mentioned you were in the Warsaw Ghetto during the uprising, what do you remember?

Hardy: For a brief spell, I was in Warsaw. I was not assigned to be in combat, only to pick up new equipment. If you can believe it, I was sent to get a single gun. At this stage of the war, I was in PJ Abt 102 [Panzerjäger Abteilung 102], which had the assault gun III. My commander ordered me to go requisition a gun he had heard was stuck in the fighting. I was now a lieutenant so this was to be my first 'mission.' German units were halted outside Warsaw as Bagration [Operation Bagration was the code name for the 1944 Soviet offensive] had completely threw us out of Russia; this was when I could say I felt the war was lost unless some miracle happened. We were beaten and dazed due to the attack.

I had heard there was fighting going on in the city, and today I understand why, when back then it made no sense. The Allies sent agents into the city and formed partisan cells that armed themselves to fight us. The Russians told them if they rose up enough, they would attack our lines again and free the city. They did just that, attacking isolated German soldiers, and officers. Planting bombs, booby-traps, and employing snipers. The first day of the revolt, several hundred Germans died at the hands of civilians.

I do not believe Warsaw was going to be defended, as the ground was not favorable for defense against the vast Red Army. Due to the amount of sabotage and killings that were happening many ad hoc German units were brought in, and some of the militias who hated the Poles. I had a special pass to enter the railhead and guide this gun to my unit. Higher-ups had a different idea, since there was no armor in the city yet, I was ordered to put together a crew and get it off the train. I did as ordered and had to use it to patrol the streets around a German HQ.

Luckily, we saw no action as it did not feel right fighting civilians, but I did hear stories about how cruel this fight was, on both sides. My gunner was a survivor of the initial actions and said men and women were shooting any German they saw, no declaration, no prisoners, no nothing. He saw a comrade beaten to death with his own rifle that women had taken from him after surrendering. This was on the first day. Sadly, I would hear many of these stories, and then see the results of the reprisals, as our forces punished anyone who rose against us. I cannot justify it, but they knew what they were getting into.

This great city was being flattened all because of a false promise and the Allies arming civilians to fight their war, which was not their fight. It still angers me that generals and politicians who made these situations got to walk away as heroes, then point fingers at those who had to respond to their creation.

You also won the Knight's Cross, how did this happen?

Hardy: Well, my men won this award, not me. I was at this time back in the 102nd and commanded a Zug [a Zug was a platoon-sized unit]. We had a good kill tally and had fought well against the Red Army. It was in March '45 that I was awarded this cross for successful leadership in the face of the enemy. At this stage of the war, it felt like this medal was being given out very often, as men were doing superhuman acts to protect their homeland. While I never had a 'sore throat' I did feel proud to have won this award, but again it was only possible due to my men.

I did not get a lavish award ceremony like the one the earlier men would have received, but that did not bother me, I was ready to get back with my men and at the enemy rather than be congratulated. As fate would have it, I did not get to wear this award for very long as the war was over by May.

Can I ask you if you witnessed any war crimes during the war?

Hardy: Sadly, it does go hand-in-hand with Germany these days does it not? Not sure if I really want to delve into this but I will tell you during war there are always those who are fanatical and believe the enemy has to be annihilated. They can be from any nation, those people are war lovers and might I say mentally unstable, battle does this to men. Now, what is a war crime? It is committing an act that is against the laws of war that you agreed to follow, meaning if you wear your nation's uniform, you took an oath to adhere to rules.

Did Germans commit crimes? Yes, I believe we did. However, I will say that some of the reprisals were within the conventions that Germany signed and were justified. The tribunals mistakenly made up new laws that did not exist before May '45, and then held men accountable to these, which was wrong. I do not want to sound like I am justifying crimes, but many times there is more to these than what historians understand.

An example is Warsaw, the people rose against the occupation, which was against the rules of war, and we shot men, women and children who sometimes committed very sadistic acts on German soldiers, sometimes who were kids themselves. So who is the criminal? Two wrongs do not make a right, but what would other nations do? I think history shows what other nations did, the same thing. The English murdered millions of Indians who opposed their rule during the war, yet all we hear is about German misdeeds.

Even my beloved America has its hands dirty, I just read about all the German prisoners who died right after the war on Eisenhower's orders. If true, this is a huge war crime unparalleled in history. I knew some of the men who never came back, and rumors were they died at the hands of vengeful Allies. My point is, do not be fanatical, fanaticism leads to bad things happening, just as the SS believed executing partisan hostages would stop further attacks, or partisans killing collaborators to put fear in anyone else being friendly to the enemy. Killing begets more killing.

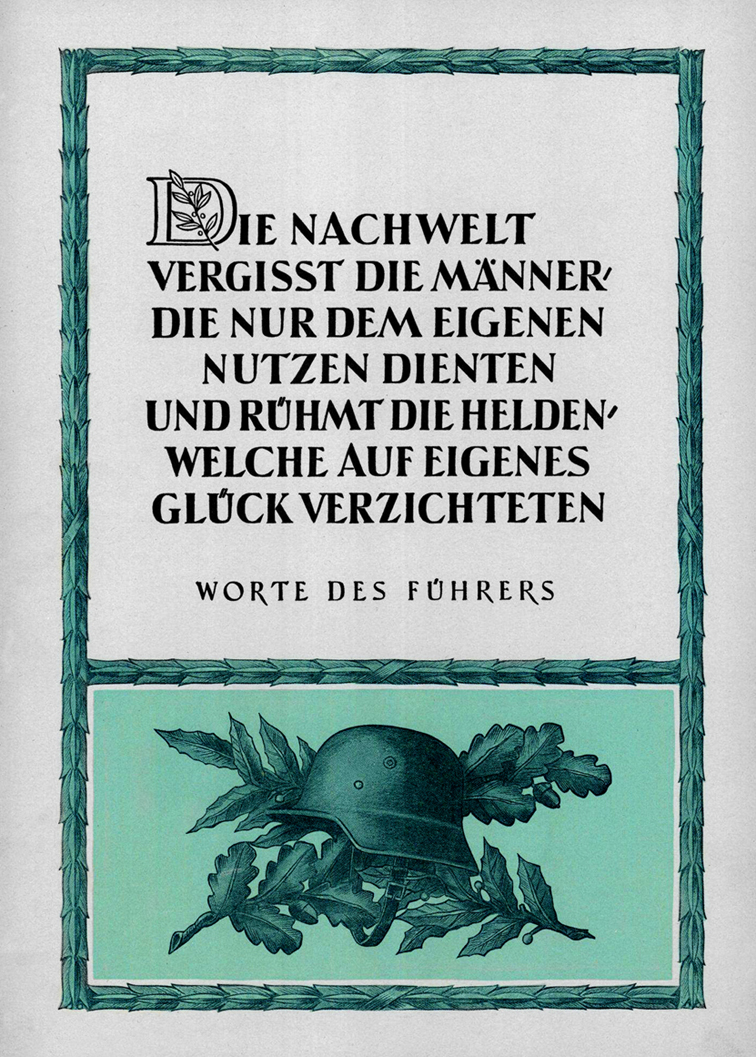

[Above: This says:

'Future generations

forget the men

who work only for their own benefit

and praises the heroes

who renounced their own happiness

Words of the Führer']