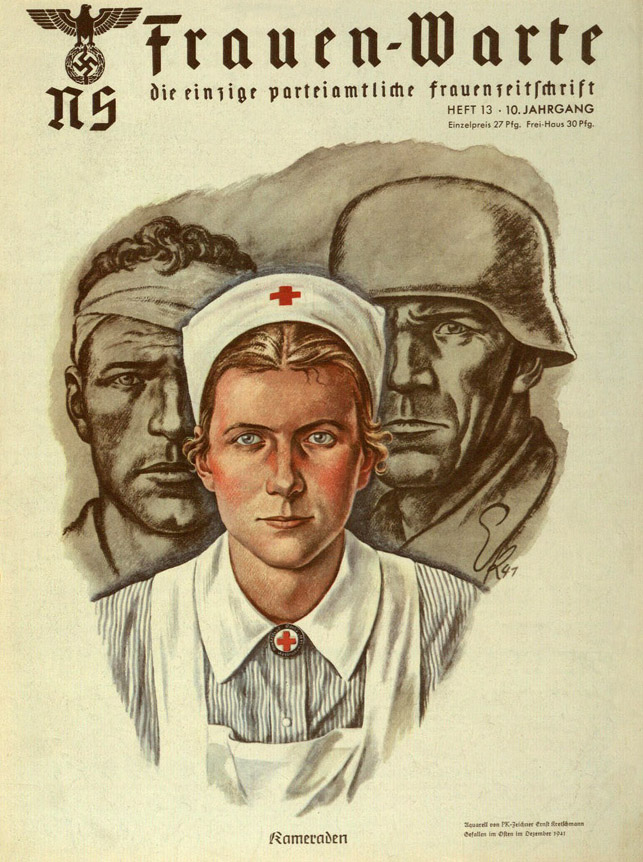

This is a 1991 interview done in Worms, Germany, with German Red Cross (D.R.K.) nurse Trude Keller, 1943-45.

This is a 1991 interview done in Worms, Germany, with German Red Cross (D.R.K.) nurse Trude Keller, 1943-45.

Thanks for meeting with me; I would like to ask you what life was like before you joined the Red Cross.

Trude: Yes, born in 1919 I grew up a city girl, going to school and getting my education close by. I remember the election of Hitler, and how most people did not know what to think of him. We were spared the street fights and chaos of the time of struggle, my parents wanted nothing to do with it. My father worked as a forester and did well for us; my mother was a librarian part time. Times were not that bad for us, but many Germans felt Hitler would make life better for them.

Nothing really changed for us until 1934; they started building roads and improving buildings. Our local church received a makeover that made us very happy, paid for by the state. I would see more and more uniforms being worn, and a NSDAP leader came to our home, I think it was 1936. He asked if there was anything the party could do for my father but he declined and said politics did not interest him. I think he was trying to get him to join the party. He returned the next week and gave my father a dagger to go with his forestry uniform. It left a good impression on him, but he still did not want to join.

My father’s pay was increased, and we had the chance in 1938 to go on a paid vacation to Italy, this was happening to all German workers, paid for the state. By now, I was in training to be a nurse, and attending school for this. The beach was very nice; it was a good time to be German. The Italians treated us very well.

Life in Germany had improved for most everyone; Hitler was hugely popular as this success was his doing. I was able to attend school at no cost, if we were sick there was very little cost for care, and food was plentiful and very affordable, no one went hungry. Germany appeared to be a transformed nation.

Were you in the BDM?

Trude: No, since my family was un-political my parents had no desire to see me join. I would have if I was younger, but by the time it was popular, I was too old to care. I had friends who joined and loved being a part of this. I had to endure all the stories they told of camping, skiing, swimming, and traveling that they got to do. It seemed like it did a lot for the average German girl.

How did you come to the Red Cross?

Trude: I finished all my schooling and passed my exams to work in a hospital. I started in June 1939 working in a section that helped people with broken bones. We would see many of these since the roads were built and people drove faster. When the war started it did not affect us too much, it was almost a distant affair. We worried being close to the French border, but army units were staffing the front. I did hear the French invaded German territory, and held it near Alsace Lorraine, this was worrisome.

Life went on as in peacetime. Life stayed normal for me, I met a young man who served in a Luftwaffe Flak battery in Frankfort, so we saw each other often, and then married in December 1942. By the start of 1943, the war was dragging on and not going well, total war was declared and Germany fully mobilized to fight. It was suggested I join the Red Cross to do my part. I was a fully licensed nurse who now could work in surgery or any other medical field.

I was accepted after going through the background screenings, being assigned to the Luftwaffe. The Red Cross would send you where they needed you, but they did ask for a preference, I of course wanted to stay close, so I was sent to Clichy, in Paris, which was not close. It was a large Luftwaffe hospital, but actually cared for everyone including the French. We mostly treated sickness and not many war wounds, as this was a quiet area. Some were brought from the east if German hospitals were overcrowded.

Were you in Paris during the invasion? Did you see any bombing raids?

Trude: Yes, I was in this hospital from 1943 to August 1944. The Allies did bomb parts of Paris, and we treated French civilians wounded in these attacks. They mostly hit the railyards and some factories, but at night, they were less accurate and hit houses, killing and wounding many. It was hard seeing the children brought in. The Luftwaffe had very little in flak as Paris was considered an open city not to be defended. France was bombed heavily by their friends, I read more than 50k were killed during the war.

In June, we saw lots of wounded coming from the invasions front. There were horrible wounds, and our doctors were over stretched, more had to be brought in from other nations to aid us. We had two from Sweden, two from Spain, and three from Switzerland along with their nurses so it was sometimes hard to communicate. This hospital treated Allied soldiers as well. We were hearing that the ambulances were being attacked, which was upsetting. One example I remember drove from Lisieux to Paris and was shot up wounding the driver and killing an English soldier who was already wounded.

We would send the long term wounded back to Germany, and we heard the resistance was attacking the trains the wounded were on. It was a scary time, we had many French working with us and we became distrusting of them as we were hearing of attacks on German personnel. My husband’s letters worried me as he spoke of the never-ending bombing raids on Germany; sometimes I would go outside and would see the smoke trails of the bombers wondering if he would shoot at them. I could hear the sounds of battle all those kilometers away in Normandy on some days.

From the wounded soldiers I spoke with, I could tell the battle was not going well, they talked about being overwhelmed by airpower, and armor. Many were anxious to get back to comrades to fight. We had several of the elite paratroopers here. By the beginning of August, news was coming in that the Allies broke out and were heading to Paris. Panic gripped us, and we debated staying or leaving.

We were told to make ready to leave Paris, and to ready patients to go with us, by the middle of Aug. Rumors were the resistance was sealing off the city and killing German personnel. I was assigned to a convoy of trucks that drove us to a train outside Paris; I was heading back to Germany. We read a week later Paris fell, I was happy to get out and I reunited with my husband. He was proud to also have been awarded the Iron Cross and Flak badge for downing Allied planes.

What was Germany like by this stage of the war?

Trude: We were truly a people worn out; everywhere you looked, you saw fear and despair on the faces of everyone. We tried to have dances and lots of entertainment, but these only masked the fear we had that this war was being lost. Everyone knew that after Normandy there was not much that could done. There was talk of secret weapons, alliances, and peace deals in the works to give a little hope, but many felt it was too little too late. The press always spoke of new weapons that could change the war.

All larger towns had bomb damage, and the smaller towns were overcrowded with children and families seeking shelter. The people still had faith that the Führer would be able to somehow prevail, and party leaders did a good job of always being visible to hear any worries or complaints. I was now in a Luftwaffe field hospital close to Kaiserslautern and treated many survivors of the fighting in France. I was glad to get out when I did as I heard many stories of what the resistance was doing to prisoners, even women.

In late 44, I was awarded the Red Cross medal for service I had given, and lives saved. The Allies started to just focus on bombing Germany now, and we had to treat the shot down crews, which was hard knowing they killed so many innocents, but they were soldiers and following orders. On many occasions they were deliberately driven through the towns they bombed to see the toll they wrought. I remember one such event, where they hit Mannheim; the soldiers drove the captured crew through the city to show them the laid out victims before burial. Then brought them to us to check out, before going to a camp.

We were somewhat close to the Ardennes area and could hear distant battles sometimes, the newspapers told of the hard fighting, and could not hide the defeat. We had many wounded.

What was the end of the war like for you?

Trude: It was depressing that my nation was defeated, but at the same time I was glad it was over. I had seen so much suffering and destruction that it was relief when the Americans came. My hospital had been moved close to Rothenberg am Tauber and we were full with wounded. Rumors were the Allies were shooting wounded and prisoners, but our head doctor told us it was non-sense, he said the western allies were good. In April, we were handed over to an American patrol and the first thing they asked was if we needed medicine and supplies.

Of course we did, as everything was in short supply due to roads and rails being destroyed. I was impressed with how we were treated at first. An American medic unit was sent to us, and the first thing they did was flirt with us. They took good care of our wounded, but took a few away as prisoners since they were lightly wounded. Our head protested, but to no avail. I had not heard from my husband for a few weeks and sought to find him, but the battle lines kept me from this. I was told all the western part of Germany was now in Allied hands.

In May, the French came into this area and were not very nice. I was ordered to report to a room where they were interrogating anywhere who had been stationed in France. As I went in the guard grabbed my breast hard and grinned as he left. I told the officer about my time, and that I was grabbed, he dismissed it. He informed me I was a prisoner of war, and the hospital was being closed down. When leaving the guard stopped me again, grabbed me by the breasts, and took my wedding ring.

I and other nurses were arrested and sent to a camp farther up north. We had heard rumors that vast holding camps along the Rhine were very bad and we did not want to go there. I was put in a camp for women and we were close to a large men’s camp, I could tell there was shelter and the men looked sickly. This was in June of 45 I believe, we should have been sent home per the rules of war. Other women told me others were being put in former concentration camps where typhus was killing people.

At night we would sometimes hear gunshots and we wondered what was happening, later I learned they were shooting at prisoners. I feared for my husband and myself. The Red Cross was not allowed to come in or give any aid, which was a crime. Most all people in my camp were under-nourished and sick; the French seemed to not care one bit. Sometimes locals would try to bring us food, but they were pushed away. At night, someone would try to throw bread over the fences, which we appreciated.

This went on for weeks; we would hear calls to escape, telling us that they were killing the prisoners. Finally, in July the commander met with us, and told us no one was being killed, but some had died due to sickness, and that we should all be released soon. This gave us hope, and the food got better. Pulled aside with other former nurses, they gave us supplies to start treating our sick. Most sickness was related to poor diet and easily fixed with better food that we finally received. I was shocked to see children being brought in; their crime was being in the Hitler Youth.

They were very scared and cried often; we had to calm them down and tell everything would be OK. They told horror stories of what was happening, whole town would be forced to come out, anyone who had a medal or badge, or any job in the government was seized. People were turning against each other, eager to show the Allies who was a Nazi. More and more women were brought to this camp, and for the first time I heard about the rapes the Allies were committing. A young girl was brought in who was in the BDM; she showed signs of trauma in her genitals and was in a state of shock. This was outrageous.

In September, all medical personnel were released and allowed to return home. I sought my husband, and after searching for a few weeks learned, he was a prisoner of the Americans, and would soon be released. Luckily for us he was drafted and did not volunteer so that made a big difference. We reunited in November of 45, we felt very lucky to have survived.