This interview was done in 1989 in Fehmarn (a small island off the northeast coast of Germany) with SS Division Leibstandarte officer Erhard Guhrs. Like so many others, Guhrs was accused of war crimes after the war.

This interview was done in 1989 in Fehmarn (a small island off the northeast coast of Germany) with SS Division Leibstandarte officer Erhard Guhrs. Like so many others, Guhrs was accused of war crimes after the war.

Thank you for allowing me to arrange a meeting with you, it is nice to meet you. I wanted to start by asking you, since you were in the bodyguard division (the 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler or SS Division Leibstandarte began as Adolf Hitler's personal bodyguard), how did it feel to be in such an elite organization?

Erhard: Yes my boy, my comrades say you are quite fascinated by our history, so that is always nice to see. Many in my own homeland view us as misled criminals who deserve only jail. This only shows how misled and propagandized they have become, what a shame.

Yes I was in the LAH, and served with some of the best men this nation has ever brought forth. We were young, enthusiastic, and wanted to serve our country. I ended up in the heavy panzergrenadier battalion of the LAH, a man named Joachim Peiper was my commander. Perhaps he may sound familiar to you?

I served with the LAH in the east, in Italy, and in Normandy. Due to almost losing my arm in Normandy I was in the hospital, unfit for action. Even though I was in the LAH during wartime, we still thought of ourselves, and were viewed, as an elite group of men. If one was in the SS, he was seen as part of an elite force, if he was in the LAH, then he was the top of the elite.

I understand you were an officer in the Waffen-SS, how did you become an officer in such an elite organization?

Erhard: The Waffen-SS was different from the army in that anyone could rise to be an officer. The army was still steeped in class structure, so you normally had to come from a high social class to be admitted into officer school. Education played into it as well, but normally a lowly bread maker would never become an officer.

The Waffen-SS looked at the man overall, regardless of where he came from or his background. If you had the leadership ability, and prowess in the field, you could either be recommended, or apply. It was strict for admittance; there were tests that had to be passed first.

To become an officer one had to be suggested by a commander to attend, or appointed by a higher up. If you did well in the field you would get noticed. A psychological exam had to be done as well and this was hard as they looked for any reason to dismiss you. This was dropped later in the war.

Once placed into an officer course you would go to a special school set up as a barracks, where the training was focused on leadership, order execution, law, dealing with soldiers and the problems you can be faced with and so on. To finally become an officer in the Waffen-SS meant you were a sharp cut above, and I will tell you the girls fawned over us as we walked the town.

You fought on the Eastern Front; can I ask what it was like for you?

Erhard: Yes, but first I want to tell you how we ended up there, if you do not already know. Stalin had Russia posed to expand west, it was their stated aim to have a worldwide revolution, by force if need be. They already proved a willingness to take land by force or threats. Germany was a barrier to Stalin, and in a sense shielded Europe from attack.

As Europe hid in fear, cowering behind America for protection from Russia, Germany prevented their worst fears. Hitler had proper intelligence that showed an attack was going to happen at some point, so he hit first. The vast amount of war material that was captured was truly mind-numbing.

Much of it was used by us against Russia, or given to our allies. The food rations had to be given to the population who was hurt by the scorched earth policy. History does not remember today that Stalin ordered all areas destroyed. This meant all animals, buildings, dams, wells, towns, and villages; there was no care for the people.

They viewed anyone who stayed behind and did not retreat as a traitor. It is ironic also that history forgets millions who did stay behind and helped Germany in every way. The myth of slave labor was put in place to hide that so many willingly came to us for help, and then helped us.

The fighting in the east was hard and the weather made it even harder. I was at Kharkov and I had never seen anywhere so cold, snowy, and miserable. The population was evacuating, which made traveling on the dirt roads even harder. Our armor had a very hard time. Russia might have been nice to see as far as scenery, but I have no plans to ever go back there.

You mentioned you served under Joachim Peiper, what kind of person was he?

Erhard: He was someone you would have liked to meet; he was jovial, friendly, and liked by most everyone. He was a very young officer; he owed a large part of his rise to being an early SS man, and on the staff of the Reichsführer-SS. Matter of fact he met Sigurd as she was a personal secretary, like Hedwig was. Lina is the one who introduced them.

I was surprised to see he was married when I first met him, he seemed so young. He was an excellent leader, and he led by example. I can tell you one time when he was with the panzer regiment he was disappointed they were not catching onto his style of advance, so he used his old battalion to show them how it was done.

He was very patient, and liked to see all sides, yet practical and demanded we all respect each other's views. He was not afraid to say things that might have been hard back then. He told me personally in 1943 he felt the war was lost. He saw no way Germany could overcome all the forces arrayed against us.

He understood as a National Socialist that the dark forces in the world succeeded in uniting against Germany and wanted our blood since we exposed them. Yet in spite of this he said we must fight to slow the hordes of the east, which would devour our women and enslave the children. From what we know of what happened in the east, he was right.

I am proud to say I knew him and called him a friend, my hope is that someday we will find the cowards who killed him. He was murdered in his home by what we presume to be left over communist fighters. They killed him, his dog, and then burned down his home. I can not help to believe that there has to be a higher purpose to all the suffering and pain we went through. Because of this faith, I know our persecutors will one day face a final account for what they did.

They seem to have gotten away with it; all the while the press makes us targets of hate and attacks. They say we committed all the crimes and killed Jews, but we will be blameless in the end.

Did you fight during the Kursk battle? If so what was it like?

Erhard: Yes I was there, still in the heavy panzergrenadier battalion, we were involved in the thick of the fighting. I remember it was a hot July when it started, and very humid. Our mood was full of confidence, as for us this was the last battle to decide victory. We either would win, or the end would come for us. So every man fought like a devil to bring victory.

The Soviets had built many fronts to face our attack, so we had to break ring after ring. We succeeded in this and punched holes through these strong defenses. They hit with all they had, and we took losses, but our sheer will pushed them back. For the first time in awhile I remember thinking we would come out on top. We took many prisoners who told of their units collapsing, and the Red army being finished.

This made us fight even harder, it was hard to sleep, and we drank coffee or tea like water. The air battles and artillery was a constant reminder that fighting was raging. For us the fate of Europe was being decided in the east with this fight, and we did not want to miss it.

The SS Division Leibstandarte moved deeper into the belly of the defense, and even with the Russian reserves being committed we kept on moving. It was slow progress against the Pakfronts (the Pakfront was a defensive military tactic developed by the German forces on the Eastern Front) and trenches, but we still moved hill to hill, or trench to trench. We used grenades often, throwing them over the sides as we came to a trench. Our engineers had to quickly make paths for us to move on.

In the end it was all for nothing, the events in Italy proved disastrous for if they fell the Allies had a clear path in the south. The Fuhrer had no choice but to pull divisions out of the fight to go to Italy. Many of us agree we had victory within grasp if we could have had more time.

What was your time like in Italy? I have read crimes were committed there, is that the truth?

Erhard: Oh yes, crimes were committed, just not by German forces. The SS Division Leibstandarte was ordered to disengage at Kursk, and start march preparations for Italy. The men were confused but did their duty to the letter. Our equipment had to be made ready for rail transport and that took awhile.

When we arrived we received orders to disarm the Italians, by force if need be. Some did intend to fight; a fat officer told Joachim [Peiper] he would wipe us out if we did not leave. I remember him saying “then the friend decides to become the enemy”, we prepared to go into action.

There were plenty of Italians who welcomed us, and wanted no fighting at all, they tempered our anger at the ones who did. We had many who acted as emissaries to make peace, and many soldiers surrendered. I have to tell you that here we came into terrorists who were communists and hiding out.

We started having German personnel attacked, some wounded, some killed, some taken hostages. This angered our leaders, and in good faith they tried to work to solve the problem without fighting, we had just come from a large battle and needed to refit and rest. There was no time to deal with terrorists.

They refused to just go away in peace, they started using mortars on convoys, and snipers would take shots at Germans. They wanted money for the return of hostages. Finally we received orders to move into a town where they were holed up, and as soon as we came close they opened fire from the homes. Our only defense was to bring up artillery to hit the positions.

Now the problem was that this town was being lived in, the civilians either could not leave or would not. Our guns opened fire on any and all positions the terrorists were shooting from. This caused fires and severe damage, civilians had been hit, but we did not know this, we assumed the towns people were gone or in on it.

This turned into a wild fight, going house-to-house, that is when we saw civilians. So now we had to be very careful, and allies were sent to start a cease fire. It was agreed upon, and the hostages were free, plus the body of a soldier who was shot in the back of the head.

As we started to give orders to withdraw these terrorists hit us again with mortars. Our leaders were furious and as more shots came at us the order to open fire was given. We tried to pinpoint where they were but it was hard, and several houses were destroyed in an effort to get the enemy.

More men were put into the fight, and we finally drove them out and secured the town, whose mayor was very angry. I believe the terrorists later killed him and the priest because they worked with us to bring in soldiers who had heard the fighting and came to see what they could do.

Many of the soldiers we were sent to disarm decided to join the new army Mussolini was forming. They took an oath, and were set free. We watched them closely as we did not trust them. I remember Joachim [Peiper] ordered fliers to be sent out warning any acts against us will be met with force of all types.

There was no more word about this fight until the 60s; communists came forward claiming we killed hundreds of women and children. I saw only one civilian who had been killed by artillery, not hundreds. Some of the civilians actively aided the terrorists as I saw them shooting at us. No uniform whatsoever.

This was a simple case of illegal fighters moving into a town, being given refuge and a base of operations. When we moved in to secure hostages we were fired on, and returned fire. The terrorists used civilians as human shields, and then cried foul when we did not know this, and fired on them.

There is no doubt some innocent people died, and that is tragic, but we committed no crimes. We had to engage the enemy on ground they chose; it was either shoot back or be killed. Today the political forces in the world want everyone to think we just went around and savagely attacked civilians, this is not the truth.

Other than this instance, our time in Italy was nice and relaxing. We got along well with the Italians, and trained some of the men who joined Mussolini. There was even an SS division created for them. We ate well, relaxed, and enjoyed the company as best the war would allow.

You were part of the Invasion Front, what was it like for you there?

Ehrhard: Well, I almost lost my arm due to the battle so I would say it was not so good. From what I remember, the LAH arrived in sections to the front, due to Allied air power; it took days to move only a few km. We were always being updated on the situation, and I remember thinking there is no way to win this.

If victory was to be won, the landings had to be repulsed like at Dieppe. I knew if the Allies got a foothold then it was over. It was wishful thinking that our small forces would be enough to push them back. I bet you didn't know that the landings came up against very little resistance.

I know men who were stationed on the coast, and they had no great strength, in some places the Allies just walked ashore. They quickly overcame any light resistance, and moved several km inland on the first day. It was only when the Waffen-SS was free to hit them that they tasted losses.

We had a hard time moving during the day, you always had to have an observer to watch for enemy planes. Those damn guys shot anything moving, we had prisoners who they killed doing this. They bragged about their precision, so did they do these things on purpose? They even shot civilians whom we had to take care of, or bury.

Because of the strength of the Allies, we were forced to mainly stay on the defensive; the few times we did attack were successful until the naval guns hit us. The boys of the LAH gave the enemy hell when they attacked us. We had weapons that could knock out any Allied tank; we reaped a bountiful harvest of their armor.

The battle for Normandy went on for two months but we could not stop the Allies with their material might. They had no shortage of men, guns, bullets, fuel, and food. We, on the other hand, had our rear lines always under attack, either from the air, or partisans.

I was wounded for the 7th time, and this time the doctors wanted to take my arm. I was able to keep it, and I had lost my two brothers and so by Führer decree all surviving boys of a family were released from frontline duty. So for me the frontline was to be left behind, and I was put into officer reserve.

How do you feel about the charges that the Waffen-SS was a criminal organization?

Erhard: I believe all the charges to be totally baseless and political in nature. If they would have waited to bring charges after we were gone then they might have succeeded. They accused us when we could still defend ourselves, at least in the west; in the east it was impossible. In Italy for example, it was the Italian courts that looked at the evidence, and saw there was none.

They declared there was no evidence to show civilians had been killed, those who were killed chose their fate by fighting us, which was a crime. In France it was the same thing, we had defenders, often French, who said no crime was committed. To shoot partisans as a reprisal was legal, and all sides did it.

All over Europe, even the Americans, released us when the true evidence was looked at, even Joachim [Peiper] was released. Many who had been sentenced to death were freed, as the evidence showed no crimes were committed. Even Malmedy is not a crime, Americans attacked or ran from their guards. Arriving men opened fire on the melee not knowing they supposedly had surrendered.

In every case I have heard of and looked over, there was no evidence of executing civilians. Only terrorists, partisans, and saboteurs were ever executed, and within the rules of war. I suppose someday they will just make the criminal acts legal so they can then again charge us for murder.

I can tell you as a German officer, if any man would have done anything like this, there would have been severe consequences. We had men punished just for harassing or stealing from civilians. We wanted to have good relations with the civilians, not make them our enemies.

What about the concentration camps, do you feel anything wrong went on there?

Erhard: Young one, I was not in a camp so I can not speak about them. I have known comrades who were there and if you asked them they would tell you nothing bad at all went on. They would tell you all of the prisoners were well treated in spite of what the prisoners said, unless they purposely broke rules.

It was the end of the war that caused the trouble, and where many did indeed die in the camps. You might be told that it was the Allies who brought about the poor conditions in the camps they found. I was with the Waffen-SS, and we had nothing to do with these places, we served our nation in a time of war, and fought with honor. There is nothing more to say about the myth of what happened in the camps.

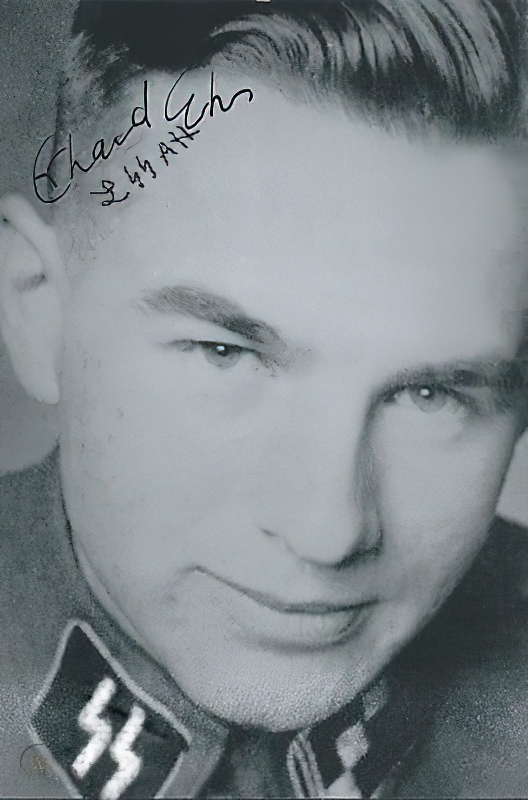

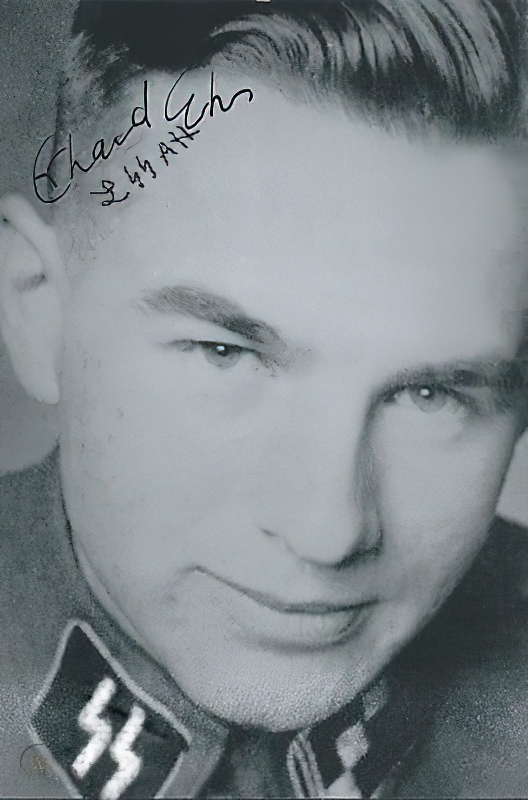

[Above: Erhard Guhrs, an old soldier from the war that never ended.]