Interview with Siegfried Milius, Commander of the elite SS-Fallschirmjäger-Battalion 500/600, 1988, USA.

[Above: Siegfried Milius.]

Interview with Siegfried Milius, Commander of the elite SS-Fallschirmjäger-Battalion 500/600, 1988, USA.

[Above: Siegfried Milius.]

It is a pleasure to meet you, and thank you for taking the time to speak with me. I would like to ask you first off what attracted you to join the SS?

Siegfried: I want to say thanks for having me here in Ohio at this fine reenactment. I never thought I would see Americans in SS uniforms. It is interesting to me that you are recreating our unit to reenact war. Very strange. So let us begin, I joined the SS because it was the best of the best in Germany. I was offered good pay, it fulfilled the military requirement, and the uniforms were a symbol of pride in the traditions of our people. There was nothing sinister about it.

I was taken in when the requirements were very stringent, you had to prove your German ancestry back to the 1700s, as many Jews had come to Germany after that time and mixed with German blood to blend in. One had to be in excellent health, a good height, good teeth, and intelligent. The battery of tests one had to take was at times aggravating, but it was a very elite, small group.

I was accepted into the SS TV unit [SS-Totenkopfverbände-Ed.], and did my training in and around Dachau, Germany.

Did you see the Dachau concentration camp?

Siegfried: Yes, there was no way to avoid it; Dachau housed a very large complex. There was the main camp, and all around were the SS training and administrative areas including a hospital. I remember seeing prisoners in all these areas working while unguarded. In many respects it was like any other prison, good prisoners were given jobs with no supervision. Hardened lawbreakers had to be watched more closely, but there were very few guards.

I would like to comment to you how clean the camp complex was, flowers and a large garden gave the appearance of a quiet place and not a prison. The prisoners were largely political criminals who had committed crimes or instigation of terror against the new National Socialist state. I met a prisoner who was serving 5 years for handing out communist leaflets, and then attacked the person who turned him in. He worked in our barracks area keeping the grounds clean.

What was the mood in Germany like when war was declared on Poland?

Siegfried: The mood was very somber; no one wanted war, especially with what we learned about the first war and how hard it was on the people. You see, even though Poland was being accused of border incursions and threats, we wanted peace with them. I know there were areas on the border that had seen attacks, but we knew these were isolated, and more the work of criminals instead of the Polish government.

The Führer wanted all lands returned to Germany that had been taken, which most agreed was a very reasonable request and any nation in our shoes would seek the same. Poland was pushed by the British to refuse and this turned into heated rhetoric, where they made wild threats that they would march on Berlin. We mobilized in August and never thought this would turn into a shooting war.

It was with sadness and fear that we donned the field grey uniforms to go fight. When the Allies declared war on us, the feeling was 'here we go again'.

I know you are most famous for being in the very elite SS paratrooper battalions. Can you talk about how you came to be in this group?

Siegfried: Yes, I was aware before the war that talk was going on about a SS TV paratrooper unit, but it was scrapped as there was not much interest, and the Luftwaffe paratroopers were still being built and tested. In 1943, it was remembered I had sat in on conversations regarding building a paratrooper group, so I was approached about the idea and agreed it would work.

It was to be an all-volunteer unit, with a small cadre of soldiers who had broken military law and would be allowed to redeem themselves. I want to dispel a myth that seems very prevalent today; this unit was not a penal unit. We did not take in men who had been convicted of serious crimes. A serious crime in the SS could be as simple as stealing a loaf of bread from a civilian up to an illegal killing. Some offenses like rape and murder would bring a firing squad.

Our men were those who perhaps were charged with dereliction of duty like sleeping on watch, missing roll call, or harassing civilians in occupied areas. The most severe I had was a soldier who shot himself due to combat fatigue. These were all brave men, some of whom just needed a second chance to prove their honor. This new battalion offered just that, my men appreciated the opportunity.

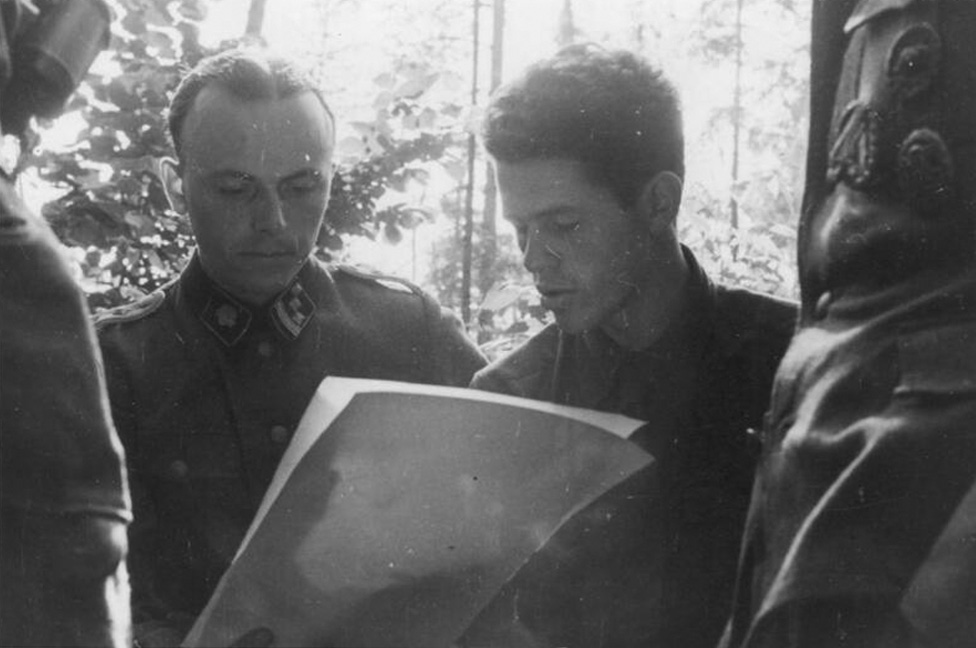

[Above: Siegfried Milius (far left, middle) with his SS-Fallschirmjäger.]

You were in operation Rosselsprung, can you tell me what this was like?

Siegfried: Yes, as you may know this was an operation to capture Tito [leader of Yugoslavian communist partisans-Ed.] . To give you some background on this: in 1941 we had to invade this area to quell pro-Allied forces and stop a threat of invasion. This area had been very pro-Russian and anti-German even before the first war. When we conquered the area, our leaders thought it wise to release most POWs and allow them to return home, and we built home-guard units to keep peace. This was a failure; they started fighting each other when we left.

Communists moved in and organized, so that by 1943 the Balkans had become a haven for deserters, the lawless, and the Allies. Sabotage was a problem, but was controlled by the local friendly militias. The main worry was an invasion on a very open front. It was decided the newly formed SS paratroopers would lead this surprise raid.

We did not have very long to prepare for this drop and the lack of intelligence really hurt us. We had to rely on secondhand information regarding the location of Tito's cave and other areas. It was known the Allies had camps around Drvar [a town located in Bosnia and Herzegovina-Ed.]that they used for launching attacks on friendly units, or helping aircrews. The whole region belonged to enemies who had to go. Our attack would be in the morning and in two waves, early morning and 5 hours later.

The Luftwaffe bombed areas around Drvar first, causing lots of dust and smoke, which hampered us. This was in a valley so the smoke had nowhere to go. This also alerted the partisans we were coming. When the men landed, they were met with hundreds of front line weapons which cut them down. The Allies had Tito well-supplied and organized, reinforcements poured in as soon as we landed.

We had ground units to aid us as well, converging from every direction to trap and destroy this enemy. The big problem was we had a force of perhaps 20 thousand facing 200 thousand. Our ground units were parts of the Prinz Eugene [Division] and many ad hoc heer [army] and foreign units. They were stalled and held up by stiff resistance, which our intelligence did not account for.

It was with superhuman will that our men were able to hold on in Drvar, we had better aim and were able to destroy many hotspots of the partisans, moving from area to area to clear them. This operation was very bloody for our men. The partisans took no prisoners, and killed men in defenseless positions. A group dropped right by Tito's cave and as soon as they came down were all shot down with no calls for surrender first. A captured partisan confirmed this. A few men had been shot when captured.

We chased Tito, as prisoners confirmed he was running, but to no avail. Our units were too understrength to keep going up against the reinforcements Tito could call in. We even had to deal with Allied aircraft, our leaders sent us bombers, but could not spare any fighters so the Allies hounded us. I had a narrow escape during a bombing raid. During this time some of the civilians gave us water and food. I have always wondered if the partisans killed them later.

Speaking of this, did you see any war crimes during this time?

Siegfried: Surprisingly this battle was fought clean considering whom we fought. Even this glider episode is not really a war crime, however if it was us, we would have called for surrender first, and if they fired first we would have annihilated them. One good thing for us was this area was seething with hatred, and if the Soviets ever left the area, it would erupt again. The militias who were friendly to us fought against our enemies and it was a bloody affair. We would turn over any captured partisan to the local militias usually; who I am sure dealt with them in the same way the partisans would have dealt with them.

This was a very nasty business, but in this battle, we treated the partisans as enemy forces since they were in essence led by Allied commanders, and wore a semblance of uniforms. We took many prisoners from this operation, and I do not know of any shootings of partisans in reprisal for a killing. I cannot speak about the ground units, but the history books do not record any claims of war crimes.

How long did the battle last?

Siegfried: This operation lasted just a few days total. The ground units scattered the partisans and drove Tito to an Allied-held island we found out. By June 1944 the whole of our fronts had collapsed. The Allies invaded Normandy, Russia destroyed army group middle, and Rome fell. Therefore, our hard efforts and losses meant nothing in the end. This operation was, in military terms, a failure, as we missed Tito.

We chased away the partisans, killing and capturing a vast amount, but as soon as we left for other duties, they came right back and reorganized like nothing happened. By the fall and winter of '44 the Russians had taken this area largely with the help of Tito. Then they committed some of the worst crimes against Germans and our allies that history has forgotten.

[Above: SS-Hauptsturmführer Siegfried Milius with SS-Obersturmbannführer Otto Skorzeny (left) during the defense of Frankfurt-on-the-Oder.]

What was the end of the war like?

Siegfried: After Drvar, we shipped to other areas as a fire brigade and we planned a jump on Finnish territory. It was canceled, as there was no need to take the island as the Russians were advancing too fast for it to make a difference. My new unit, the 600, was tasked with rear guard actions against the enemy. We were in constant action from December '44 until the end of the war.

I was amazed at the amount of material the Russians had with them, we could knock out 100 tanks, but 200 more came forward to replace them. Our forces were understrength, worn out, and lacked supplies. America too had what seemed unlimited resources; I always say America is the land of impossible possibilities. The vast material advantage the Allies possessed doomed our small nation in the end.

The new unit took part in the Ardennes Offensive, and gave a very good account of itself, but this offensive, while actually making military sense by splitting the Allies like in 1940, was disorganized and some units were not even at half strength. We resented being used in a ground role, but in those days, one had to do their duty whatever it meant. After we failed to break the Allied lines, the unit went back to the east front to face the Russians. We would halt an attack, causing heavy losses, then be moved to another section of the front and do the same thing. This went on up to April '45, when all attention was on Berlin, we fell back and surrendered to the Americans.

How did the Americans treat you when you surrendered?

Siegfried: By the standards of the Geneva Convention, we were treated badly. We were kept as criminals, denied food and water and some were beaten and tortured to get confessions regarding crimes that were never committed. An instance I remember was of a young soldier who was threatened with death or the Russians if he did not admit to witnessing a shooting of a French family during the Ardennes battles, he was under my command and they wanted to blame me. It was dropped.

This type of incident was common, we would be entrenched in an area, which sometimes had farms or houses with civilians who did not leave, and the Americans would shell the whole area, killing the civilians. Then they blamed SS troops for murder. However, we tried to avoid civilian areas during battle, if we could, for this reason. We would have no reason to kill peaceful people and always wanted good relations with the populations we stayed with. It only made sense as we could buy food and seek shelter without fear of retaliation. Heaven forbid if there was a pretty girl around, she had many suitors.

I saw many of our soldiers had their possessions stolen by Americans; there is a very big market now for German militaria that was looted and stolen after the war, I see some of it here. This was a crime under the laws we adhered to. We never allowed ourselves to take things from surrendered enemies. Many of my men were kept in pens with very little food, the Red Cross was forbidden to give aid for a while. It took months before our plight improved, but in-between many died.

I understand the Allies were hard on the Germans, especially the SS as the crimes that you are accused of angered Allied soldiers. Do you think that justifies some of your treatment?

Siegfried: Oh, you are breaching a sensitive subject. While I cannot speak for every member of the German armed forces, I can tell you my men behaved well, and on every front I fought I only saw cases of Allied crimes, not German. We had strict orders, and the only time I saw civilians killed was if they were saboteurs or partisans. When German forces enacted a reprisal it was within the rules of war, maybe sometimes muddied, but always a reaction to an attack against us. All prisoners of war were treated well, even partisans, as I mentioned, were taken prisoner. Where by law they could have been shot or hung.

Therefore, for me the Allied treatment of Germans was a horrendous crime, propaganda fueled their feelings; everything that showed death or destruction was spun as a crime. Even the camps, those dead prisoners shown to us all were the result of the Allies knocking out the ways to get food and medicine to them, causing horrendous late war outbreaks of typhus. Even Germans were dying from malnutrition and disease. Hundreds of thousands died after the war due to the Allies. Yet, we only hear of the supposed crimes of the Germans. We stand innocent.

[Above: Siegfried Milius (left) with his SS-Fallschirmjäger.]