Interview with Heinrich 'Hein' Greil, member of Großdeutschland guard battalion, regiment, and later part of the 2nd Panzer Division. Fought in France, Yugoslavia, Russia, Normandy, and the Ardennes. Germania Club, 1987.

[Above: Commander of the guard regiment 'Grossdeutschland' Heinrich Hogrebe (far left) welcomes Reich Minister Joseph Goebbels.

Also shown here is General Karl Lorenz (to the right of Goebbels), General Joachim von Kortzfleisch (to the right of Lorenz), December 1, 1944. Click to enlarge.]

Thanks for letting me sit down with you to ask a few questions about your wartime experience. I understand you were in the Großdeutschland Division, how did you end up there?

Hein: Well, when I went in it was not a division, it was the guard battalion. I went into the military in 1938 right after my six months in the labor service. I enlisted in March which I remember was cold and damp. I joined the army as I wanted to serve my homeland, and it paved the way for better careers.

Now, I started as just a regular infantry soldier and passed all the training and courses and was promoted to private. How I came to regiment GD [Großdeutschland], I was asked to report with other men to an officer who was at our base. He was looking for men who were interested in the ceremonial duties in Berlin.

This interested me as it seemed to offer a chance to see the big city and the pretty girls I heard were there. I answered his questions and later was told I had been accepted to training. By the time I made it to Berlin the battalion had been expanded to a regiment and the war had started.

It was here that I was bitterly disappointed in my situation. You see I was a young idealist, and I wanted to be at the front. GD was not to be part of the actions in Poland, and I remember the men being very upset as we bore the name of Germany. The officers had to calm us down; one even chastised us for wanting war and fighting.

I was in the infantry company of GD and we were detached and sent west for additional training that winter. France, in all their wisdom, had declared war on Germany citing our aggression against Poland. We knew we were going to be fighting them at some point, and many of us figured it would happen in the spring.

What was it like during the French campaign?

Hein: Ah it was a hard battle, the British were there also, and our forces did a move that still astounds men to this day. The main force struck through the forests in the Ardennes completely taking the enemy by surprise. This split them in two, and as they turned to respond they were beaten.

Regiment GD was with the 10th Panzer Division during this time and this is when I remember becoming interested in Panzers. Those black uniforms really stood out sitting on top of those steel machines. We fought the British and French in many battles, forcing them to Dunkirk. We had to stop right before they were surrounded and captured. In my mind this was what cost us the war.

If we would have captured them all, Britain would not have been able to continue. I remember seeing tens of thousands of prisoners going to the rear. We treated them as friends too, there was no hate. I remember speaking to a French soldier who called out in German for a smoke.

We shook hands, showed photos, and I gave him a few smokes for his ride to the rear. There were many wounded French who received care from us, I saw this all over. There were hospitals set up just to care for the French civilians and soldiers who needed it. We willingly gave away our food as well, the civilians who clogged the roads were in poor shape sometimes, and we helped them.

After the resumption of the offensive on Dunkirk, we saw they all got away; many were in disbelief that our leaders let this happen. Today I still think Hitler did this to show the British we were not their enemies. When the town was secured we moved to the south and met slight resistance. I will tell you the feeling of victory was strong, we did in a short time what our fathers did not do in four years.

My unit was to take and occupy a town called Lyon, and we met scattered resistance points. We started to see the French go as far as to welcome us as they needed food, water and supplies. We set to work helping repair what we could. We even ran into negroes who the French coaxed into fighting for them.

They did try to fight at times, but their resistance was half-hearted. Those who did fight were reckless and quickly overrun. I saw many of their fallen; some were shot for running away it appeared. It seemed odd to us that these soldiers were dying for France, which occupied their nation. The loyalty was admirable, however this war had nothing to do with them, or Africa. Many were collected, checked for war crimes, and sent back to Africa.

They seemed more a problem for the French than to us. We took the surrender of many of them, and then came the accusations that they committed acts against the civilians. Some civilians spoke to the officers in the SS unit that was with us, rumors were some of these negroes attacked a woman.

The mayor was livid, I remember seeing this, he wanted them out of his town and he was accusing one of stealing watches from a shop. Indeed a search turned up several watches. He was held, as were others by the police to find out what happened. I will tell you too, I remember seeing a few who were said to have been killed by their officer for a mutiny.

War can be a confusing affair that makes no sense.

After all this was over we were able to relax and enjoy the weather, we helped the vast amount of refugees get settled back home. We stayed in France the rest of the year and something the history books don’t tell you is that we helped the French with everything from rebuilding, to planting. We then were moved for action in the Balkans.

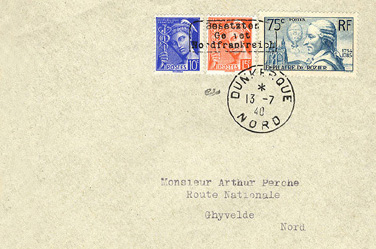

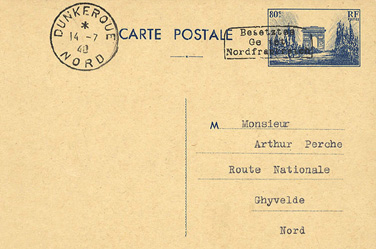

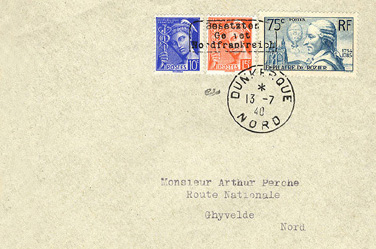

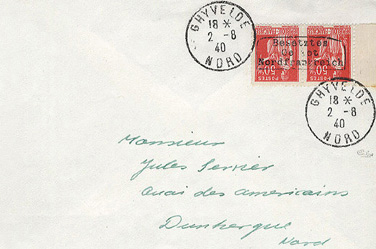

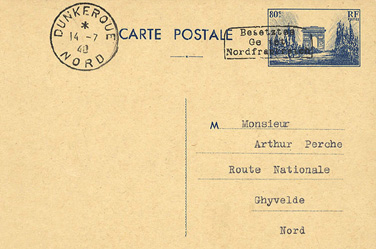

[Above: On July 1, 1940 very rare examples of postage stamps were born. French stamps handstamped with the overprint 'Besetztes/Gebiet Nordfrankreich' (Occupied Territory Northern France).

There were two types of overprints, which were ordered by the German military commander in Dunkirk, France, for civilian use (July 1st - August 9th). Click to enlarge.]

[Above: Top left - here is an example on an envelope of the Type I Dunkirk overprint. The German authorities used the same postage rate as the previous French authorities, so here we see a 10c and 90c (to reach the 100 centime/1 franc letter rate) stamp tied by the German overprint. The cancels themselves are of the old French post office. On the right we see three French stamps (10c+15c+75c=100 centime/1 franc) tied by the Dunkirk overprint. Click to enlarge.]

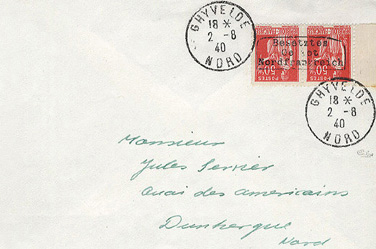

[Above: Top left - here is an example of an even rarer Dunkirk overprint: note that the French stamps (50c+50c) are inverted. This doubles the value and is rarely found. Lastly, on the right, we see an overprinted postcard of 80c (the postcard rate is cheaper than the envelope rate). Click to enlarge.]

What was the campaign like in the Balkans?

Hein: We were sent to Romania and we were told we were there to train with the Romanian army, but we knew better. The papers spoke daily of instability in the region, and the government was asking for German help. When we went in it was fast with little opposition. The Luftwaffe did well with clearing resistance points so by the time we arrived, the soldiers had had enough.

Next we took Belgrade [Yugoslavia], and then moved on deeper into the countryside, facing very light opposition. We found out Germany had been requested to come in to stabilize the government which was in chaos. Many of the soldiers welcomed us as friends, which was a welcome change. In many towns they cheered and waved flags for us, and if one was lucky he would get a kiss from a pretty girl.

This campaign was very quick I remember, with not much fighting and nothing much to report. It was a mostly peaceful occupation, until our forces entered Greece, and then they fought a more determined foe in the British. We settled into occupation duties and got on well with the civilians.

There is one instance I remember well; it was a civilian attack on our soldiers. It was in a small town I do not recall, maybe Pancevo [Serbia]. There was some separatist groups who were opposed to rule and government, some thought maybe they were Allied agents. They captured soldiers who were sight-seeing, and then murdered them by stabbing them many times, all over their bodies. They wanted to send a message. I was present when they were brought in for burial, we were enraged.

Honest people in the town turned them in, and police were brought in to investigate. We were involved in searching homes of those pointed out, and it ended up being a nest of bandits in this group. We took men, women and children in for questions. A clear picture came out of this, they wanted to attack us to cause fear or make us hate the civilians.

A court trial was held and evidence was shown linking a group together with the murder weapons, eyewitnesses and confessions. Our commander made us sit in on these. Those found guilty of the murders or aiding were shot or hung, the towns people knew these bandits had done wrong, they even built the scaffolds for us. Like I said, war is a nasty business and those who were in on the attacks were punished.

I know you were part of Operation Barbarossa; can I ask what your experience was on the Eastern Front in the beginning?

Hein: In the beginning? Yes, in the beginning we did not go in first, we stayed behind and were used as mop-up troops. The main forces bypassed many Russian armies, which then had to be dealt with. Later we were moved to the frontline as part of the Army Group Center and took part in taking Minsk [Belarus]. The weather I remember was good for us, and we would go days with no enemy contact.

It was good in the beginning, and we took so many prisoners that we were truly baffled where they all came from. GD advanced at a good pace, always with the Luftwaffe watching the skies over our heads. We rarely saw Russian planes. Something that stands out to me was how the commissars often forced civilians to shoot at us.

Of course when this happened we had to respond as we took casualties, we were angered they would do this. I saw a man in civilian clothes cut down while firing at the recon section. A commissar was captured hiding in a house nearby, and it was shown he forced the man to do this, he was taken to the rear, but I understand many of them were later shot due to their behavior.

I saw many of the peasants denounce the commissars and often turned them in as they hid. My platoon was sent to capture one who was hiding in a barn. He threatened the family but a youngster got away to tell us. He was captured with a radio and we found valuable papers on him. We had a newspaper team with us who wrote about it all.

I have spoken to comrades who were at the front in the beginning and they tell of the same things with these criminals. The civilians were forced to attack Germans, which made us react, which was exactly what the commissars wanted.

We learned to be very careful around the civilians and not be harsh with them, as they were many times were forced against their will to do these things. Later on the partisans were formed by Moscow, sending commissars behind the lines to organize them and force them to attack us. This turned into a separate war of its own dealing with these bandits.

Getting back to the beginning, we stayed in constant action the rest of '41 and into '42. I was badly wounded during a Russian attack on our position. The Russians launched attacks that winter on us and pushed us back. I was hit in the side and lost a lot of blood. The fire was so heavy my comrades could not help me.

I lay in the open while the fighting raged hoping I would not die; I packed my wound tightly as trained. Comrades risked themselves to get me and I was given aid and sent to the rear. I was so bad they did an emergency transfusion on me, and then sent me to a bigger hospital back home. I remember that journey taking several days by truck and train. I remember this comrade who was paranoid, he said the Russians attacked the Red Cross often, and thought we would all die.

I made it safe and sound and it took several months for me to heal, I was hit in the intestines and kidney and had shattered rib bones, I still feel it today. I was kept out of the war for all of 1942, healing and serving in the replacement unit doing light chores. I was awarded the Assault Badge, Iron Cross, and Wound Badge. I was looked upon as a front fighter veteran.

You are young and like the pretty girls, so you understand, while I was recovering I met a girl who worked at a movie theater. We saw every new movie that came out first, and would then go out to dinner and then walks. Love in wartime was hard as I had to leave her and then found out she took up with someone else who was stationed close by.

You served in the 2nd Panzer Division, how did you go from GD to the regular army?

Hein: It is a strange thing, we fought alongside the 2nd in Russia, and I admired the Panzer crews. They always got to ride where they went, we had to march. In the hospital I was with a comrade who was on a light Panzer, and said there were better Panzers coming. He told me I should switch over to Panzers.

He suggested I should try to come over to them, but GD was an elite unit and I had no interest in leaving. I did ask about joining the GD Panzer unit, but was told no. As my chores bore on I became very bored, and wanted to get back to the front. It just so happened I bumped into a Panzer officer one night while out drinking, he was this comrade's commander.

As we talked he spoke about how they terrorized the Russian tanks and were close comrades who enjoyed good times together. He said he could pull some strings and get me moved over to the Panzer arm. I took that step and asked to be transferred to the 2nd Panzer. Whatever he did worked, I was allowed to go.

After some criticism from my friends I reported for training. I spent most of 1943 learning all about Panzers, from how they drive, fire, and get repaired. This training I still remember fresh as we had to go out in the worst weather and simulate a busted track and take it off and replace it.

You have not lived until you replace a Panzer track in 40 degree rainstorms. The training was very hard, but prepared us for the harsh realities we would later face. When all the training was completed I was welcomed into Panzer Regiment 3, and was welcomed by General [Vollrath] Lübbe. I joined right when the division was recouping from [Operation] Citadel, and was then attacked and pushed back.

I was quickly assigned to a Panzer, where usually one was assessed before joining a crew. We were knocked out by a hit to the track, here is where the training helped, with the help of a repair truck, and we repaired our home in a downpour with lots of swearing and yelling at the parts.

It was a welcome order to be sent to France for rest and refit, I was very happy, and I remember thinking the war was not so bad for me. I had been on a holiday leave for a year, training for almost a year, and now a vacation back to France. Little did I know this only put me in the Normandy battle.

[Above: An instructor from Großdeutschland Division (his sleeve shows him to be the holder of FOUR Tank Destruction Badges!) teaching NCOs about T-34 weak spots. Ukraine, 1943.]

What was it like being on the invasion front; can you tell me what the enemy was like?

Hein: Yes, at first France was very nice, we were close to the coast and had a good time. We received leave and could go into Paris to sightsee or enjoy the shows. The people were very kind to us, and many comrades met girls to keep them company. I went home to see family and here is where I saw bombing devastation for the first time.

I recall the training was done often, especially with us new hands so we were not a problem. We were close to Amiens [France] I believe, and the people would come out to watch us practice. When the invasion happened on the 6th of June, we were frustrated to say the least.

We were held back and when finally allowed to advance the Allies knocked out every bridge to Normandy. We had to go on wild detours to reach the front which took days. We had to drive at night since the Allies were in the air all day. We could hear the fighting and felt helpless knowing our comrades needed us.

I was assigned to a Panzer 4 with the long gun, and was the loader. We could not wait to get into action; I was so young and foolish then. We finally made it in time to meet British units, what I saw was disorganization amid vast Allied advantages. The German units in Normandy were spread out too thin. On the maps we could see huge holes in our lines. Germany had too few divisions to face the Allies.

More of our reinforcements came and we were ready to start attacking but then we met their naval fire. They hit everything and anything, and we could not move. They had spotters who were watching our assembly points. Anytime we tried to attack they opened up devastating fire. We were forced to stay on the defense and fight their attacks.

We did very well at this, and knocked out our first Sherman [American tank]. We took a hit, but we had extra armor on our Panzer that stopped it from penetrating. We stayed in the defense for most of the time. We fought both the British and Canadians. We took our fair share of Canadians prisoner and got along well with them. Some seemed very cold and full of hate; their propaganda made us out to be monsters and bad soldiers.

I was hit in the leg by a piece of shrapnel and was sent to the rear to be fixed-up. I saw Canadian prisoners at the aid station along with French civilians who had been wounded. I felt bad for the civilians, they were caught in a war and their liberators bombed them without mercy.

I spoke to a Canadian who spoke French, and we shared cigarettes and talked about home. After the war they claimed we shot their prisoners but that is nonsense, we would have no reason to and I only saw very fair treatment of them. Even this soldier I spoke to said he was treated very well by all the German soldiers he met.

I was later in combat against them; I believe it was a town called Authie. I was unwillingly attached to the SS Panzers. We were ordered to assist them while picking up our repaired Panzer. They surprised a Canadian unit who put up a hell of a fight, but were caught in the open in the town square.

We fired on some who tried to run around the side of the town to ambush our comrades. This was a big feat of arms, we overtook a larger Canadian force, which later we learned was elite, and gave them a beating. They fought to the last, and would not surrender; I witnessed one soldier shoot himself as we moved in to search for wounded.

I felt bad for them as it was not necessary to die, they could have laid down their arms, I witnessed them shoot a young Hitlerjugend soldier who carried a white flag to ask for their surrender. They had a tenacity that seemed reckless and in disregard for life. French civilians had been hiding in their homes during this and came out to give aid to any soldier regardless of uniform. I remember seeing a woman who had been hit and was very angry at us.

We were low on water and they helped fill our canteens. We shared food rations as they had not gotten food for a couple days. They even searched the dead to get any food from them as well. We parked our Panzer in the town square to guard against any counterattacks, and later ate with the French. It was an odd situation but hunger made them like us.

But fortune is not always fair, the very next day we were attacked by a strong force and quickly knocked out with a shell into the transmission. We bailed out as the Panzer burned. While doing this I was hit by shrapnel from a shell of something, I was wounded yet again and put out of action. This time our medical services had been very much improved and I was moved to a hospital within an hour.

There was fear of attacks on our Red Cross, the Allies, as well as the Russians would attack ambulances, trains, and aid stations. While speaking with wounded SS Panzer men they told of the British and Canadians hitting aid stations and killing wounded.

Some were not keen to help wounded Canadians, as we had a few badly wounded ones with us. We saw them as our enemies, yes, but also as fellow soldiers and humans, so we left politics and hate out of it. I spent the next few months in Germany healing from my wounds.

You took part in the Ardennes Offensive I understand, what was it like?

Hein: Yes, that was when the war was over for me. We started out well; General [Meinrad] Lauchert gave a great speech telling us this was it. We had to win here or dire times would come to Germany. I still remember him; he was a good leader and was with us often. We started at the American lines and broke through, but had heavy fighting.

The first few days before and during the offensive, Allied planes attacked us when they saw us, we learned to hide well. Later the weather turned and took away their edge. The odds were made more even, but they still had the numerical advantage over us. I remember finding a box of tinned meat and coffee, I had won the lottery.

We rolled through towns the Americans had seized earlier, I remember seeing the faces on the civilians who had to be tired of all this. I will tell you a funny story, we stopped to make a repair and a civilian came out to tell us to leave. We asked why he was still here and he said he learned not to be on the roads as the Allies shot at everything, he didn't want his home hit. That did keep the roads clear for us at least, unlike in 1940.

We even had to deal with a few civilians who must have been emboldened by knowing the Allies were close by. They shot at our lead groups, and I understand some SS units shot them down without even arrest or trial. That was what the war had become, these are said to be war crimes now, but then it was not. Civilians are never allowed to take up arms. If they do so, then they become spies and a terrorist, what is not fair was when civilians attacked the Allies they were quickly killed but no one says anything about it.

I saw American prisoners who were marching to the rear guarded by mere boys, I thought how odd and wondered would they try to escape?

We overran many American trucks, and one had smokes so we filled up, putting them anywhere and everywhere. Our commander cursed at the lack of room, but understood the importance of such a find. I saw civilians combing over abandoned items as well, we asked if they knew where any fuel was, and they joked the Allies had plenty.

Our weak link was the lack of fuel at this time, and we had to rely on capturing American supplies. We kept going and took part in the fighting around a famous town now, Bastogne. After allowing the civilians out the town was shelled to break the American units, but they held. We had to keep going so we disengaged and moved around the town, but took artillery fire from the defenders. They had no shortage of ammunition and food which we felt.

We overcame small nests of resistance by bazooka teams or anti-tank guns, they caused us losses but we kept advancing, we were ordered to reach the Meuse [River] and take the bridges. Our main goal was getting to the port and taking supplies. If it was not for our lack of fuel we would have made it. We had guns that defeated any Allied tank; we just did not have enough of them or the fuel.

We knocked out a cleverly disguised British tank that was waiting in ambush, our commander saw it. We fired before they could do anything. I recall a wild fight happening as we took on a tank unit. We caused them heavy losses and pushed forward, but fuel was scarce, and our supplies were far behind us.

The weather cleared I remember and now the planes started after us, we ran out of fuel and that was it. We had to march back to our lines, and with the cold weather we had to shelter in anything we could find. We broke into groups and I was with my crew where we went into a home to get out of the snow.

We slept like babies I remember and stayed warm by the fireplace. The wife made us dinner which was very welcomed. A day later we were surprised by Americans who we thought were far away. At first they wanted to shoot us because of the black uniform they saw under the white parkas. Lucky for me a cool-headed officer was with them.

They did steal our medals and roughed me up while marching us to their lines, but at least the war was over. I was sent to England where I can say I received very good treatment. The British saw us as more a curiosity than a hated enemy. The camp I was at did not have the best food, but a boy who lived nearby would always come and bring us bread and other items.

The guards were relaxed as the war was clearly in the final days so they did not care. I was held there until 1946 and then allowed to return to Germany. I saw no future there and worked odd jobs until getting the idea of coming to America. So there you have it, now I am here to tell you my life’s journey.

[Above: Beautiful Großdeutschland coin 'Die Heimat Dankt den Tapferen Soldaten' (The Homeland Thanks the Brave Soldiers).]

[Above: 'GD' from Großdeutschland uniform shoulder board.]

Back to Interviews